Read this next sentence closely. At the start of the 2023 NFL season, 14 of the 32 starting quarterbacks identify as Black. OK, now go back and read it again. Of the 32 starting quarterbacks in the 2023 season of the National Football League (NFL), almost half of them are Black. If you Google that stat, each story goes on to say that’s the most brothers to ever start at the position in a single week in NFL history.

Justin Fields of the Chicago Bears was one of those 14 Black athletes playing the most highly scrutinized position in sports, and in taking on the responsibility of being a Black QB, he had a lot to carry on his shoulders. In his three initial seasons with the Bears, Fields, a former Heisman Trophy finalist at Ohio State, suffered through two different head coaches, questionable signal-calling from two different offensive coordinators and subpar staffing of his offensive and defensive lines, among other positions. In the 2022 season, Fields exhibited levels of athleticism rarely seen at the quarterback position while existing as a season-long human target who had to absorb a league-high 55 sacks. In spite of his lack of consistent protection, Fields managed to lead all QBs with 1,143 rushing yards – the second-best rushing season ever at that position.

Fields was a highlight reel to himself, by far the most brilliant element of an overall depleted Chicago team that squeaked out three wins. The Bears were bad enough to secure the No. 1 overall pick in the 2023 NFL Draft, but by the preseason of the 2023 season, Fields was getting shouted out on ESPN by analyst, and former NFL QB, Dan Orlovsky, who expected Fields to play “MVP-level football.”

Quite a few fans and media now suggest that the Bears, who for a second straight season are armed with the No. 1 pick in the Draft (gained through an offseason trade with the Carolina Panthers), move on from Fields to a shiny new star fresh out of college, namely USC star quarterback Caleb Williams – an actual Heisman Trophy winner.

Fields has his fair share of defenders, including teammates DJ Moore, Jaylon Johnson and Darnell Mooney, and even former Bears QB Jay Cutler. Nonetheless, it has yet to be proven that any quarterback can truly thrive under the Bears’ current system, and Black quarterbacks, historically, have greater mountains to climb than those of other races.

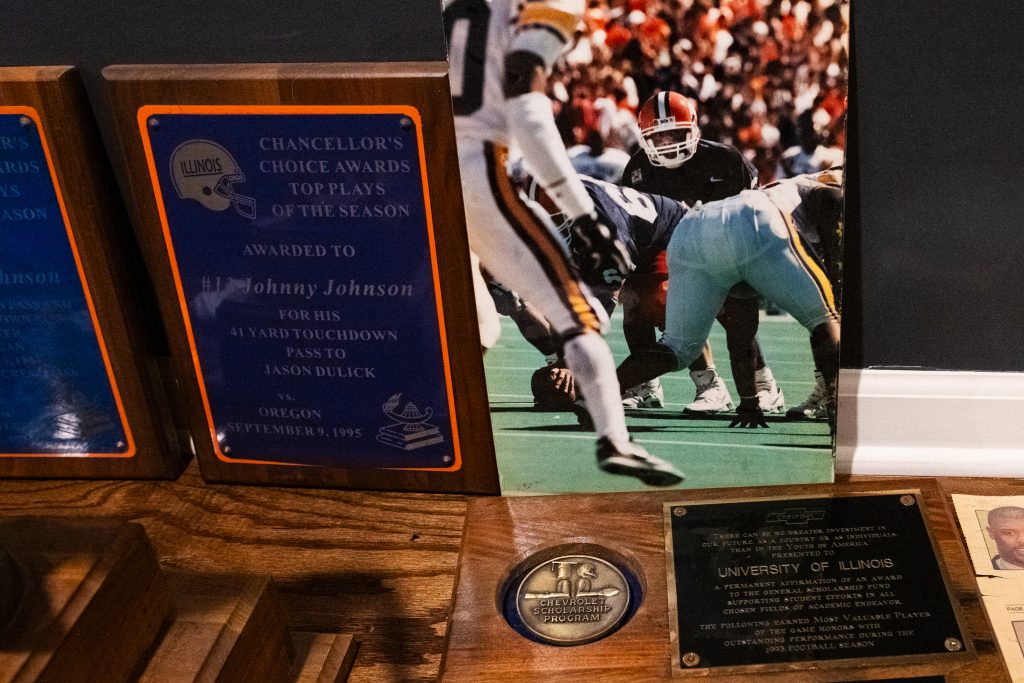

“I think he gets a bad rap, as far as what I hear in the media,” said Johnny Johnson, Jr., an All-American North Chicago High School graduate who, as quarterback, led the University of Illinois Fighting Illini to a Liberty Bowl victory in 1994, a major comeback win against the University of Michigan in 1993, and blowout wins against Iowa from 1993 through 1995.

“I see him running for his life, not able to sit down in the pocket and stay as long as he likes or read the defense,” Johnson said about Fields.

“But when he does let the ball go, he’s got a beautiful arm,” Johnson continued.

Full disclosure, Johnson is my big cousin. Affectionately called Lil’ Johnny in the family, his football career was anything but small. As a child, I remember all of us traveling to Detroit. Aunts, uncles and cousins all packed in a big Express van, excited to see Johnny take a few preseason snaps for the Lions. Johnny is a hometown hero, a legend and an All-American. Not only that, but over the years, he has proven himself to be a leader amongst his community, church and family. Lil’ Johnny is the family quarterback coach! Any young man looking to gain knowledge can contact Johnny, and he is eager to help. Once again, he is my cousin, and I have a lot of love for him. But for the remainder of this article, I will refer to him by his last name, Johnson.

Weeks after the Bears closed out their 2023 season with a 17-9 loss to the Green Bay Packers, Johnson sits in the man cave of his suburban Lake Villa home, cigar in hand, reminiscing about his glory days behind center. Today, Johnson is 51 years old and works as a planning consultant at Fidelity Investments in Deer Park, Ill. Thirty-two years ago, in 1991, he was fielding over 300 offers from major universities while looking to fulfill his dream of playing college football.

When Johnson entered the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign campus as a redshirt freshman in the fall of ‘91, Warren Moon (Houston Oilers), Rodney Peete (Detroit Lions) and Randall Cunningham (Philadelphia Eagles) were the only starting Black quarterbacks at the start of the 1991 NFL season.

When the sports talking-heads speak on Fields, it brings up uncomfortable memories for Johnson, who came up in an era when the so-called Black quarterback stigma weighed heavy on football players who worked hard to be in the position. Johnson took on the challenge and a controversial college career unfolded in front of him, playing out in the media for the public to see.

Former Illinois QB Johnny Johnson, Jr. sits down with TRiiBE culture correspondent Rome J., taking us through his experience as a Black quarterback, and why it’s hard to listen to commentary around Justin Fields.

For Johnson, who was described by sports analysts as a “scrappy” athlete who happened to throw the ball a little bit, the conversation around Black quarterbacks is always the same. “You hear [Fields] needs to make better decisions, he’s not always accurate, or finding the right receiver,” Johnson said. And of course, there’s the running.

In other words, a Black quarterback who tends to run is not a “traditional” quarterback, and they bear the brunt of that with each scouting report and assuming sports debate segment.

So, what is a traditional quarterback? Johnson rolled his eyes at the question, but he had an answer ready: slow, tall, stationary – and white.Think Ben Roethlesberger, Tom Brady, or any signal-caller with the last name Manning.

“I think with the quarterback position, you have to be the face of the program. So you have to mirror the image of the head coach and the coaching staff and what they want you to portray,” Johnson said. “I was never that, I think that was probably something that held me back a lot because I couldn’t, I just couldn’t do it.”

That being said, Fields brings a swagger and presence to the Bears’ QB position that has never been there before.

When speaking on QB1, Johnson sees untapped potential. “[Fields] pulls the ball down, he’s dropped back and, look, there’s nothing there. Somebody grabs him. He turns around. Pulls the ball down, goes and strikes up the band. Now it’s touchdown, right?” Johnson said, referring to Fields’ ability to extend plays and improvise. “Who does that? Not a lot of guys are doing that. That’s something that the NFL, I think, is becoming more knowledgeable of, but everybody’s not ready for it. The Bears, specifically, want a traditional quarterback.”

But has Fields had a fair shot? Black quarterbacks are often discarded before they have the opportunity to develop in a supportive environment. Not only that, the media conversations around “quarterbacky” quarterbacks have been dominating the narrative.

In large part because of his flash and outgoing personality, guys like Cam Newton become polarizing figures even while they become MVP candidates. Newton took a mostly dominant Carolina Panthers team to the Super Bowl in 2016, but at the first sign of declining play, he became an outcast from the franchise he helped put back on the map. Since then, he’s bounced around to an inglourious stint in New England and to an unsuccessful return to Carolina before settling to his current place as a free agent who hasn’t taken any calls from teams since being let go the second time from the Panthers in 2021.

Lamar Jackson is the odds-on favorite for this season’s NFL MVP, an award he would win for a second time. In spite of an impressive regular season record (58-19) over his first six years as a pro, the jury is still out on him, as he had only one playoff win to his credit before entering the 2023 NFL postseason with his Baltimore Ravens as the No. 1 seed in the AFC. Still, Jackson had a protracted struggle with the team that drafted him to get a competitive salary in comparison to the league’s other standouts at his position.

Jackson, an established MVP and true game-changer, suffered the temporary indignity of being in contract limbo for much of the 2023 offseason while Baltimore waited out enough time to provide a suitable offer with a suitable level of guaranteed money, a process that was much more of a struggle than anything the likes of Aaron Rodgers or Joe Burrow had to go through before receiving then-record breaking contracts.

It’s much more possible for a Black quarterback to get theirs today, more so than when Johnson had NFL ambitions in the 1990s, but it’s also still clear that Black quarterbacks don’t get the same favor and grace as their white counterparts.

“I can say that standing in the Black quarterback shoes can be a traumatic experience for any individual for multiple reasons. A lot of it has to do with a mental block that people have about us as people,” Johnson said.

Still coming into his own, Johnson had to navigate through many unfamiliar obstacles in order to live his dream. In 1992, following his redshirt freshman season, in his first decision as a sophomore, Johnson was approached by Illinois head coach Lou Tepper.

“He says, ‘hey Johnny, I always thought you’d be a great free safety. If you switch to free safety today, I’ll start you for four years,’” Johnson said, remembering the eventual defining moment of his college career.

Declining the offer, Johnson decided to sit for another year, while waiting and working for his opportunity to lead.

Johnson originally wore No. 11 when he came to Urbana-Champaign; he would give up that jersey number to help recruit Scott Weaver, an incoming freshman who could throw a perfect spiral in the rain, he recalled. Once asked by coach Tepper to change from the number he wore in high school, Johnson changed his number to the not-so-lucky No. 13, a number no one wanted, to make a name for himself.

Weaver’s presence on campus led to him being awarded the starting QB position going into the 1993-94 season, despite previous promises that Johnson would have the job. It would take a high-pressure opportunity for Johnson to prove himself, a kind of opportunity many Black quarterbacks are forced into, the kind of opportunity where Johnson was forced to perform immediately or possibly lose it all.

The Fighting Illini struggled early in the 1993-94 season, losing their first two games and threatening to lose their third against Oregon. It was in the Oregon game where the decision was made to throw Johnson in for the first snap of his college career. The Illini desperately needed a spark and he showed something in leading the team to its first score of the game after being held scoreless in the first half to the Ducks.

That one score would be the only one for Illinois in a 13-7 loss, but it was clear Johnson brought life to the offense. It was also evident by the cheers of more than 45,000 home fans in Memorial Stadium, cheers that are noticeable in watching the vintage clips of the game.

Johnson still had to win over his coach, but he made big strides in one half with the fans as well as the media, who took note of his performance.

“One person you cannot hide, you cannot hide [in] the QB position,” Johnson said.

As QB1, Johnson quickly learned what being in the spotlight as a Black quarterback meant. A quarterback carries the burden of being a model citizen on and off the field. A Black quarterback not only represents his respectable franchise or school, but also carries the unfair burden of literally being a spokesperson and representative for all Black people. This would also mean showing restraint, even when looking directly in the eyes of blatant racism.

While playing the Penn State Nittany Lions in that ‘93 season, Johnson recalls entering the stadium and looking up at a fan who spewed to him, “Johnson, you’re a nigger. Niggers don’t play quarterback.”

Johnson retold the moment with a somber look on his face.

“I couldn’t defend myself, what was I gonna do? But it gave me motivation to prove people like that wrong,” he said.

In discussing that incident, Johnson often speaks of other Black quarterbacks that he admired from that era, such as Florida State’s Charlie Ward or Colorado’s Kordell Stewart. Figuring them as birds of a feather, Johnson tried to reach out to other quarterbacks who shared his exact experience.

“I never met [Stewart],” Johnson said. “I did try to contact him one time. I spoke to his roommate. He was cool. And I was really just trying to connect with the brother to see, like, what are you going through? You know, what’s it like up there in Colorado?”

At the time, Johnson also had a person and mentor he could rely on in Illinois QB coach Greg Landry, but Landry would part ways with the school after the 1994-95 season.

Johnson had a memorable run at U of I despite many challenges. He’d become most known for his comeback victory against then No. 13-ranked Michigan in Ann Arbor in front of a national audience in 1993. Though he speaks of that time fondly, Johnson battled with his mental health during this time, he began drinking and smoking marijuana to cope. The coaching staff knew about it, but chose to ignore it, never getting Johnson the help he needed.

Despite all of that, Johnson led the Fighting Illini to a Liberty Bowl victory in December 1994, in which he threw for 250 yards and four touchdowns, earning him the Most Valuable Offensive Player and Most Valuable Player honors in a dominant 30-0 win over East Carolina. The 7-5 record that Johnson led the Illini to in that season was one of only three winning seasons the U of I had between 1992 and 2007.

While sitting with Johnson, he received a call from a former teammate, William Morris, affectionately known as “Mo,” who played inside linebacker for the Illini from 1992-96. Morris spoke definitively about what Johnson brought to the quarterback role.

“[Johnson] was a leader of men,” Morris said. “We rallied around Johnny Johnson. We believed in his talent and his skill set. I had supreme confidence walking into every game with Johnny Johnson being my quarterback. I wear it as a badge of honor, that I had a Black quarterback in college. Not only did I have a Black quarterback, I had a winner. That’s what Johnny Johnson is, a leader, and a winner.”

As the years pass, Johnson’s mark on the Illinois record books remains visible. He is currently eighth on the university’s all-time passing yards list (5,293 yards) and ninth on the all-time passing touchdown list (35 touchdowns).

While progress is happening for Black athletes at the QB position at every playing level, Black quarterbacks still fight everyday to prove that they are qualified to play behind center.

That being said, people are rooting for Justin Fields mainly because they are rooting for the brotherhood of Black quarterbacks from past to present – the ones like Lil’ Johnny who didn’t get to live out their full potential, those who never had a stable coaching staff or reliable leadership, and those who don’t fit the mold of the “traditional” quarterback and never had the chance to redefine what that is.

The post What the story of Johnny Johnson, Jr. can teach us about Justin Fields and the plight of the Black quarterback appeared first on The TRiiBE.