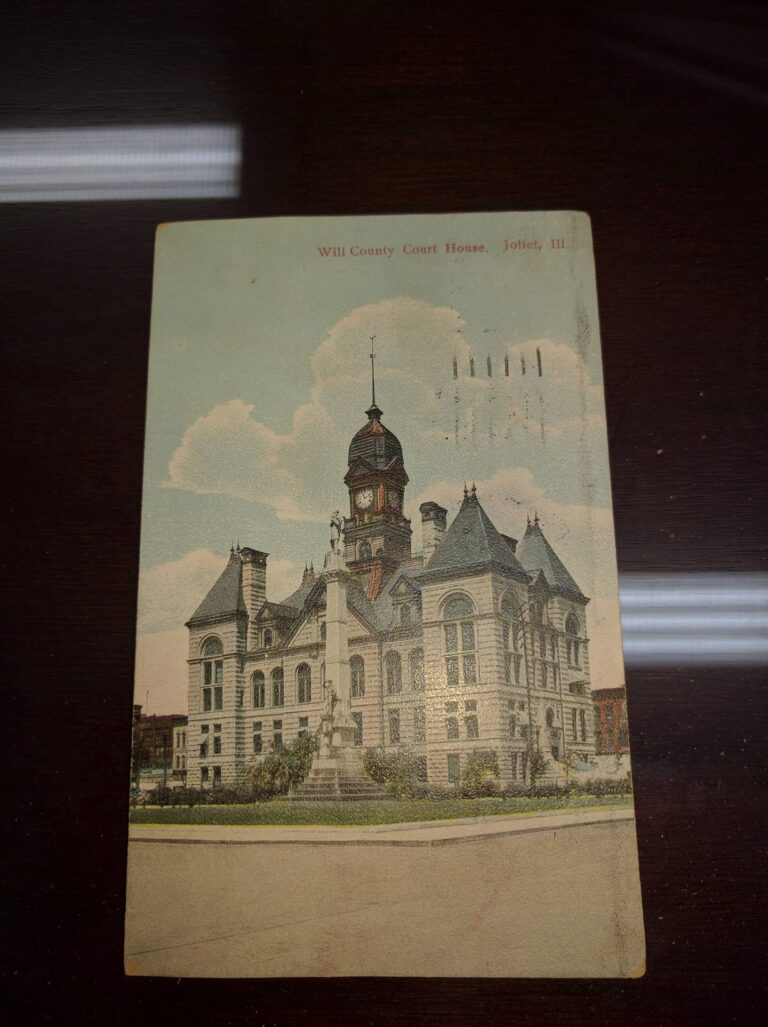

A poorly worded inscription on a plaque at the base of a monument outside the Old Will County Courthouse implies credit for the monolithic 1969 concrete structure should go to architect J.C. Cochrane, designer of Illinois Capitol and other notable buildings.

He designed the Lake County Courthouse in Crown Point, Indiana, as well, so one doesn’t have to travel all the way to Springfield to discover his busy, classical style doesn’t really fit the imposing flat stone walls of the Joliet edifice.

Advertisement

Also, Cochrane died in 1887, a major impediment to designing postmodern architecture.

In the plaque writer’s defense, Cochrane had designed an earlier, much more ornate courthouse for Will County in 1884, where the county’s legal business was handled for 80 years before it was unceremoniously demolished to pave the way for the modern structure now known as the old courthouse.

Advertisement

Architect Otto Stark, known for designing the office building at 55 W. Wacker Drive in Chicago, is credited with the design of the 1969 courthouse, which won architecture awards at the time.

Stark’s design is appropriately stark, in a style called Brutalist, not because it’s brutal, but because the French term for raw concrete is “beton brut,” and the old courthouse features plenty of that material. It was a popular style in the turbulent late ‘60s, especially for government buildings. Much like in Joliet, Lake County’s ornate 1878 courthouse in Waukegan was torn down in 1967 and replaced with a Brutalist-style successor.

A half-century later, Stark’s courthouse in Joliet is facing the same fate as its predecessor. Will County officials seem intent on demolishing it now that they have a brand new steel and glass courthouse with an award-winning design across the street.

That imminent danger helped put the Old Will County Courthouse on the 2022 list of Most Endangered Historic Places in Illinois, announced last week by the preservation advocacy group Landmarks Illinois. It joins the Eugene S. Pike House in Dan Ryan Woods on Chicago’s South Side, the Century & Consumers Buildings on South State Street in the Chicago’s Loop, Rockford’s Elks Lodge No. 64 and Gillson Park in Wilmette.

It’s the shortest list in the 25 years Landmarks Illinois has been compiling it, which is encouraging to Bonnie McDonald, the organization’s executive director. She said other resources the organization offers have helped make a dent in the number of historic structures at risk due to redevelopment or “demolition by neglect.”

“Our programs around technical assistance and grant funding and resources are growing,” she said. “Because those are growing, the number of endangered properties are shrinking.”

Since issuing the first Most Endangered list in 1995, the group has featured about 300 sites, McDonald said, with about a 50% success rate.

“We think of that as a success because these properties come to us in imminent danger,” she said. “The wrecking ball is coming. They’re deteriorating, and often times it’s seen as a last resort. To have had success with over half of them, we feel like it’s a triumph.”

Advertisement

One of their most proud triumphs isn’t far from the courthouse. The Joliet Penitentiary made the list in 2002, just months after its last inmates were transferred to other state prisons. In a Tribune story about that year’s list, Landmarks Illinois officials said the prison would be one of the group’s most difficult challenges, requiring “creative thinking to come up with an adaptable use plan for that structure.”

Now called the Old Joliet Prison Historic Site and managed by the Joliet Area Historical Museum, the site is still being stabilized with the help of millions in grant funds while also offering tours and hosting concerts, an annual haunted house and other events.

That success was largely the result of a group of active local supporters, McGrath said, a crucial element to getting on the Most Endangered list.

“We require local support,” she said, “an organization we can work with to ensure success.

“If we have a nomination from a single person, or we find there isn’t a local support base, we will work with whoever we can, but we won’t put it on the Most Endangered list.”

While lots of preservation efforts receive grants, resources and other support from Landmarks Illinois, the Most Endangered list is a way to rally public support around an effort as well as generate ideas for showcase projects. Including properties that don’t have a local support, or ones where “the wrecking ball is truly right down the road and (demolition) is a week away” would be counterproductive, McGrath said.

Advertisement

“The purpose of the list is to identify opportunities around these places and address challenges, and find solutions that can be used across the state,” she said. “These are models for other communities.

“We want it to be meaningful and to make a real difference. These are examples of larger issues around the state like public ownership and lack of public funding, owners who are using demolition by neglect, and policy issues. That’s really the purpose of this list.”

Sometimes, it doesn’t work out. Another Brutalist building, the Prentice Women’s Hospital in Chicago, appeared on the Most Endangered list for four consecutive years starting in 2009 before demolition began in 2013.

But McDonald prefers to focus on the success stories, such as Chicago’s James Thompson Center, another regular that came off the list this year after four years now that a sale and renovation plan seemingly have spared it.

The Thompson Center also is encouraging because it involves an architectural style that’s just now coming around to being considered historic.

“Not everyone sees postmodernism as historic and significant,” McDonald said. “How can something built in my lifetime be historic?

Advertisement

“This is really a story about how places gain significance for different generations. There’s a large group of people who see Brutalism and postmodernism as beautiful and significant. They tend to be younger people, under 40. It takes about 60 years for an architectural style to start to have a constituency of support.”

There’s no doubt that being easy on the eyes can help a preservation effort along. The Eugene S. Pike House in Chicago’s North Beverly neighborhood is a stately old home built in 1894 by a prosperous developer whose estate was purchased by the Forest Preserve District of Cook County in 1921, later becoming Dan Ryan Woods. According to its Landmarks listing, the district planned to use the house as a superintendent’s headquarters and it eventually became the “Watchman’s Residence” in the 1960s.

Daily Southtown

Twice-weekly

News updates from the south suburbs delivered every Monday and Wednesday

Empty for years, the house has had active preservation support from the Beverly community, but it needs extensive repairs and a Forest Preserve District effort a few years ago didn’t generate any reuse ideas.

McDonald said district officials are open to saving the structure and working with the community on a renewed effort to find another suitable use for the Pike House.

That kind of partnership isn’t evident with the Old Will County Courthouse, where government officials seem intent on demolition while a group called the Courthouse Preservation Partnership is hoping to stave off its doom.

McDonald said Landmarks Illinois still hopes to have “a constructive dialogue” and an opportunity to suggest reuse ideas for the old courthouse. But until then, adding the Brutalist structure to this year’s list is a way “to continue to bring that dialogue to the public,” she said.

Advertisement

While it may not fit the profile of most historic structures, the Brutalist courthouse in Joliet has another very important quality that makes its preservation paramount, McDonald said — the countless people who have interacted with it over its five decades.

“It tells the story of our community,” she said. “It’s part of the story of the people who live here.”

Landmarks is a weekly column by Paul Eisenberg exploring the people, places and things that have left an indelible mark on the Southland. He can be reached at peisenberg@tribpub.com.