Chicago will receive a total of $185 million in federal funding to make several of its Chicago Transit Authority and Metra stations accessible for disabled riders, officials announced Monday as part of a new program tucked into the bipartisan infrastructure law signed by President Joe Biden last year.

Combined, Chicago will receive the second-largest bundle of grants, after New York City, under a provision in the massive $1 trillion bill that sets aside $1.75 billion for transit agencies to improve their stations’ accessibility. That program was championed by U.S. Sen. Tammy Duckworth, a Democrat from Illinois, who modeled it after CTA’s own 20-year plan to place elevators in all stations.

Advertisement

“It’s absolutely urgently needed,” Duckworth said in a phone interview. “This is going to be a significant investment in making sure that our mass transit stations will become fully accessible to all.”

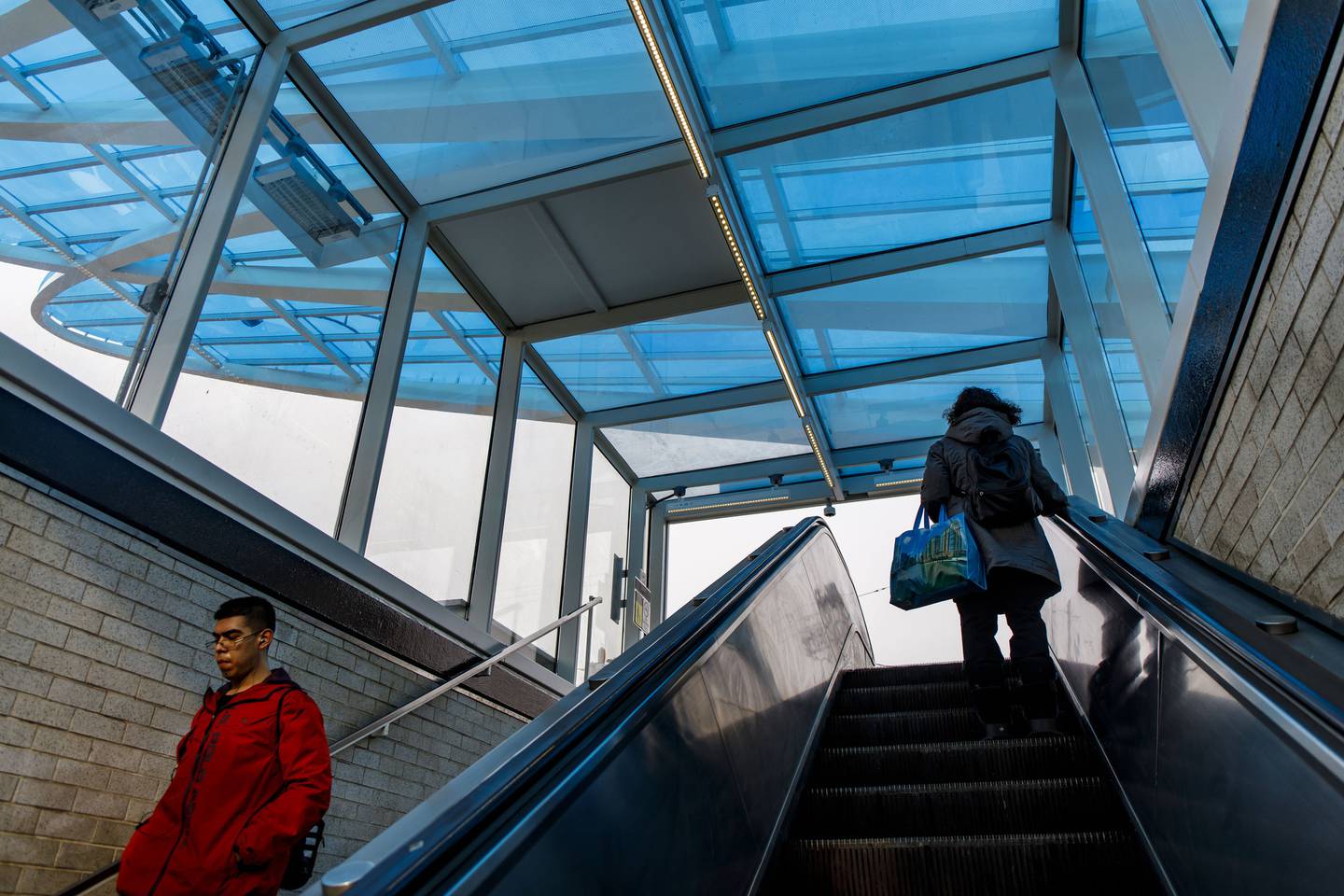

The largest award for the city will be $118.5 million, for the CTA to modernize its Irving Park, Belmont and Pulaski stations to be fully compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act. Those stops were built more than 50 years ago and are among 42 CTA stations that are not ADA-compliant, but the construction projects envisioned for those three include elevators, ramp upgrades and improved signs.

Advertisement

Then another $37.6 million will improve accessibility at the 59th/60th Street Station on the Metra Electric line, including reconstructing the street entrances and platform enhancements. The last $29 million will go toward making the 95th Street-Chicago State University station — built in the 1920s — fully ADA-accessible via installing elevators, adding a pedestrian tunnel and pathways to connections and redoing the platform.

“The urgency for individual human beings is stunning. It’s life-changing,” Paul Kincaid, a spokesman for the Federal Transit Administration within the U.S. Department of Transportation, told the Tribune. “One of the hallmarks of public transportation is that everyone gets a chance to ride.”

The new grants — a total of 15 in nine states — must be used for improving inaccessible rail facilities that were built before the 1990 signing of the ADA, which largely allowed older buildings without accommodations to be grandfathered in if they predated the law. More than 900 such legacy stations remain inaccessible today, the federal government estimates.

Signed into law by President George H.W. Bush, the ADA prohibited discrimination against Americans with disabilities and required all newly constructed buildings to be fully accessible. At the time, less than 10% of CTA stations complied with accessibility standards, and that percentage is now over 70%.

But that still leaves 42 of Chicago’s 145 “L” stations inaccessible today and lacking upgrades for decades, with some last renovated in the 1930s and a handful that have not been substantially improved since the late 1800s and early 1900s, according to CTA records.

Duckworth, who lost her legs in a combat helicopter crash in Iraq, said that lack of progress is abysmal.

“It’s a sorry state,” Duckworth said. “I mean, I don’t take the ‘L’ in Chicago because I never know if a station is going to be fully accessible for my wheelchair or not. That’s why I created the … act at the federal level.”

In 2018, CTA President Dorval Carter Jr. and then-Mayor Rahm Emanuel unveiled the transit agency’s All Stations Accessibility Program, or ASAP, an effort to make all of the CTA’s stations accessible by 2038. Duckworth balked at the slow timeline, but Carter said his hands were tied unless more funding streams opened.

Advertisement

So the then-freshman senator introduced a bill to implement the ASAP initiative on a federal scale. That legislation was superseded by the $1.75 billion accessibility program in the federal infrastructure bill — only half the amount Duckworth wanted, but a good start nonetheless, she said.

Kincaid said the Biden administration will continue vetting projects submitted through the grant program for the next few years, under the bipartisan infrastructure law, which sunsets in 2026. However, the federal government will also “encourage” local governments to put up as much funding as they can too, he said.

“The best time for this would have been years ago, right?” Kincaid said. “But the second best time is tomorrow.”