By Stacy M. Brown

Black Press USA Senior National Correspondent

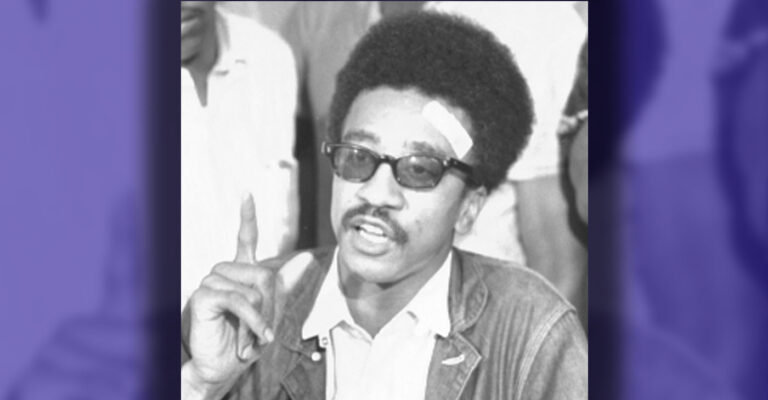

Rap Brown did not wait for permission to define himself. Long before federal agents called him a menace and politicians wrote laws in his name, he was a young man from Baton Rouge who believed the country needed an honest confrontation with its own history. Long before he died at 82 in a federal medical facility in North Carolina, he had already become Imam Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin, a name he adopted after turning to Islam inside Attica.

“Violence is necessary. Violence is a part of America’s culture. It is as American as cherry pie,” he said during the height of the Black Power movement.

Brown grew up fighting his way to and from school. He was sent to a Catholic orphanage for discipline and learned early that resistance required both strength and wit. He earned the nickname “Rap” for his unmatched wordplay on the streets of Baton Rouge. His political direction began with his older brother, Ed Brown, who introduced him to the Nonviolent Action Group at Howard University, where Brown met future movement leaders like Courtland Cox, Muriel Tillinghast, and Stokely Carmichael. Carmichael later described him as a serious and strong brother whose calm presence inspired confidence.

By 1967, Brown became chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee at just 23 and immediately pushed the group to remove the word “nonviolent” from its name. His speeches captured the rage of Black communities across America. He reminded audiences that Black people had waited a century after emancipation for promises that never came. “Black folk built America, and if it don’t come around, we’re gonna burn America down,” he told crowds from college campuses to street corners.

Federal authorities responded with surveillance and suppression. FBI COINTELPRO documents placed him on a list of four men considered top targets to disrupt. Congress passed the federal anti-riot statute in 1968 and openly called it the “H. Rap Brown Law.” When asked for comment, Brown rejected the idea that a statute could contain widespread fury. “We don’t control anybody,” he said. “The Black people are rebelling.”

His arrest record grew as law enforcement pursued him across states. In 1971, he was wounded in a police shootout in New York, denied the charges, and was convicted of robbery and assault. He served five years in Attica. That time behind bars reshaped him. The foreword to “Die Nigger Die” describes his spiritual shift as a change rooted in self-discipline and study, noting that he embraced Islam and emerged committed to building a moral path forward.

After his release, now known as Imam Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin, he settled in Atlanta’s West End. He founded a mosque, ran a small store, organized youth programs, and worked to rid the neighborhood of drugs. He preached self-control and responsibility. He explained that the Muslim’s duty began with teaching oneself and then guiding one’s family, adding that successful struggle required remembrance of the Creator along with the doing of good deeds.

To many in Atlanta, he became a trusted spiritual leader. A local Islamic civic leader called him a pillar of the Muslim community. To law enforcement, he remained the militant figure they had pursued in the 1960s. FBI agents infiltrated his religious circle. The New York Times reported that some investigations began shortly after the first World Trade Center bombing in 1993.

In 2000, two Fulton County deputies were shot while serving a warrant. One died. The surviving deputy identified Imam Al-Amin. He denied involvement. Federal inmate Otis Jackson later confessed repeatedly and under oath to being the shooter. The Fulton County District Attorney’s Conviction Integrity Unit interviewed Jackson but never moved to vacate the conviction.

After Imam Al-Amin died in federal custody, CAIR and its Georgia chapter renewed their call for justice. CAIR National Executive Director Nihad Awad issued a statement that read, “To God we belong, and to Him we return. Imam Jamil Al-Amin was a hero of the civil rights movement and a victim of injustice who passed away in prison, jailed for a crime he did not commit.” Awad added that the justice system should reopen the case and clear his name.

Brown’s life spanned eras of open segregation, mass rebellion, state repression, spiritual transformation, and community leadership. He understood that freedom movements required structure and purpose. In one of his clearest reflections on struggle, he said liberation movements had to rest on political principles that gave meaning and substance to the lives of the masses. “And it is this struggle,” he said, “that advances the creation of a people’s ideology.”