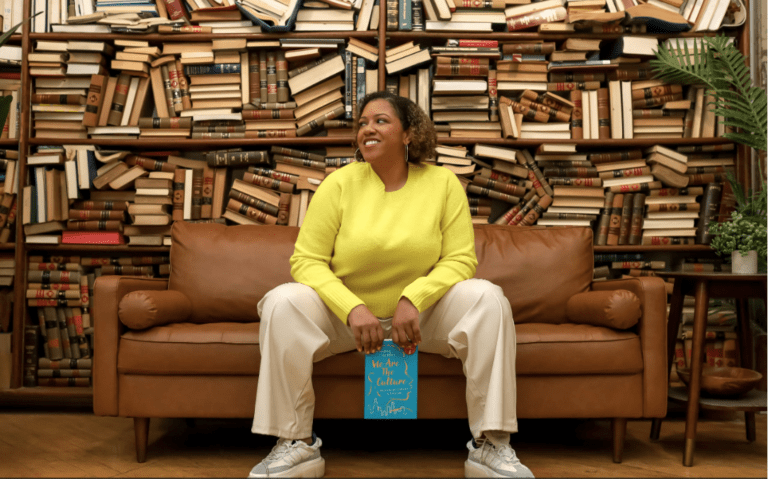

Creative, joyful and determined. Those are the three words that best describe Black Chicagoans, according to South Side native Arionne Nettles. She’s an author, freelance culture reporter and lecturer at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism.

On April 16, Nettles is releasing her first book, We Are The Culture: Black Chicago’s Influence on Everything, which pays homage to Black people, places and institutions that have shaped Chicago and American pop culture at large.

“Chicagoans don’t like people talking crazy or silly about our city. As Black Chicagoans, we know that the city is joy, creativity and determination, regardless of whatever else is going on,” Nettles said.

From an early age, Nettles has always been fully immersed in Black history and Black Chicago history thanks to lessons from her teachers, grandmother, mother and community. “I’m always learning new things, but there was never a time in my community where Black history wasn’t uplifted or celebrated,” she said.

Her family’s story and South Side upbringing are also woven throughout We Are the Culture. Nettle’s maternal grandparents owned a tavern in the Black Belt and opened a recording company called Bea & Baby Records in 1955. Musical artists on their roster included Little Mac, Hound Dog Taylor, Homesick James, and Eddie Boyd.

Black Chicago’s influence constantly permeates pop culture but is often missing from important mainstream conversations. Through We Are the Culture, Nettles gives Black Chicago its flowers by uplifting the origin stories of some of the city’s most important and celebrated art forms and cultural institutions, such as the Blues, Johnson Publishing Company, The Chicago Defender, Soul Train and much more.

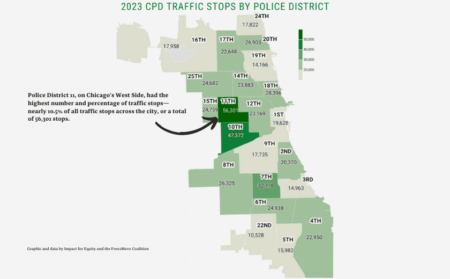

Think back to the 50th anniversary of hip-hop, and the tributes curated at mainstream award shows in 2023. Chicago artists were notably missing from the main stage at the 2023 Grammy Awards. However, the 2023 BET Awards included Chief Keef in its Hip-Hop 50 lineup, where he performed “Faneto” on the main stage.

Chicago’s drill scene, which artists like Chief Keef pioneered, now has international appeal, Nettles writes in We Are The Culture.

“It’s an art form that is an expression of the pressures that society has created. Drill didn’t cause poverty, segregation or any of those things. Young people can express themselves through drill music,” Nettles told The TRiiBE.

While writing We Are The Culture, Nettles poured over hundreds of historical documents at places like the Chicago Public Library. Narrowing it down to what would become the final chapters of her book was difficult, but she hopes readers will see what she offers in We Are The Culture as a snack.

“Hopefully, people will read this as a snack, like a snack of how great the city is. Everything just can’t fit in a book. When you think about music, for example, that could be 15 books to tell the story of Black music in Chicago adequately,” she explained.

The TRiiBE spoke with Nettles to learn about writing her first book, being a Black Chicagoan and the importance of Black Chicago’s contributions to American pop culture.

(This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity).

A book by author Arionne Nettles that is about the influence Black Chicago has had on everythingIn ‘We Are The Culture,’ Arionne Nettles discusses Black Chicago’s undeniable impact on pop culture. Photo by Ajah Jolly.

The TRiiBE: Congratulations on finishing your book! I remember you tweeting through the writing process last year. How does it feel to be done?

Arionne Nettles: It feels really surreal. It started off as me just having an idea and wanting to do something that made sense for me because I’m a Chicagoan, and this is the type of stuff I research and report on as a journalist. Throughout the writing process, you connect to it in a way I wasn’t expecting. So now that it is complete, it feels surreal in a way. It’s done, like, it is a book, a book that you can pick up, that you can hold, and that feels very wild to say.

As Black Chicagoans, we know how important Black Chicago is to American pop culture and how sometimes we aren’t recognized for our influence. Was there any difficulty getting publishers to sign on to your idea?

AN: Yeah, so for that reason, I specifically only queried local Chicago publishers. I felt this was a Chicago book and didn’t think other people would get it. I talked to a couple of book agents and bigger publishing houses. You have to have an agent and can’t query them yourself. The agents would say, ‘what is it that you’re trying to say?’ They didn’t get it, and I’m, like, ‘I just told you, Chicago influenced everything in pop culture. That’s it. That’s the thesis.’ That’s what it is, and they did not seem to feel what I was saying. So I was, like, okay, I am just going to query local, Chicago-based places because I think they’ll get it. I just want somebody to get it. I don’t want to have to keep explaining myself.

Part of pitching the book is explaining yourself repeatedly, but I didn’t want to anymore. I said what I said: Black Chicagoans, we influenced all of this, and that is what the book will talk about. I just wanted a publisher who got it. My editor is a Black woman. She got it. So we just had a really lovely process where she helped guide me through a lot of it.

I’m pleased that I did a local book for a local audience. If people from other places like the book, that would be amazing, but it’s not necessarily for anybody but us. Sometimes, you just gotta make stuff just for us. Sometimes we get to do stuff and say, ‘No, this is for us.’ It’s like the beauty of local news. At the end of the day, if my community is happy with something, then I did well. I did my job.

Black Chicago has such a rich history. We Are The Culture includes so many historical and cultural moments, from the Chicago Defender’s launch to Michael Jordan and the 1990’s Chicago Bulls. Was it hard to narrow down what to focus on, and does that mean we’ll see more books like this one from you?

AN: This book is a good appetizer platter. Since turning in the last substantial draft, I have learned much more. So it’s like I’m continuously learning and being exposed to more, not even intentionally but just literally being a Black Chicagoan and living my life. Moving through the city, doing regular stuff like going to museums, taking dance classes, meeting people, talking to friends, like just moving through this city, I learn more and more beautiful things.

Not another installment of this book, but more culture books that touch on many of these themes and tell more of these stories because they are so fun to tell.

Your grandmother played a significant role in your upbringing and taught you many life lessons. Who were the others in your family life besides your grandmother who kept you in the know about Black Chicago history?

AN: That’s so interesting. So my mom was a teacher who always kept me abreast of stuff like that, and so did my teachers. I went to a Chicago Public School where all my teachers were Black. Black History Month was a big deal and Black History Month celebrations were my favorite time of year.

I became obsessed with people who were not Martin Luther King, Jr. I remember there was one period when I was very much obsessed with Phillis Wheatley. I also went through a phase where I did oratory contests reciting Sojourner Truth’s “Ain’t I A Woman?” speech. It was my favorite thing to get up on stage and do. There was never a time in my community where Black history wasn’t uplifted and celebrated.

Within this book, you’ve also woven in your own family’s unique history and their involvement in the Blues scene. Did you know that you’d include your family’s story as you mapped out chapters in the book?

AN: So I knew I was gonna weave in some stuff. I knew about my family’s connection to Chicago Blues. As I was working on the book, I knew I wanted to include part of that, but then I kind of realized that I wanted it to be woven in throughout. So many of us are Great Migration grandbabies; we’re not far removed from that period.

I feel like, in many ways, my family is just the quintessential Black Chicago family. I have the same stories you’d hear if you talked to so many other Black families. That’s why I wanted to include them. I felt like we had that in common.

In journalism, you’re taught that if you have someone exceptional, that person should be your lede. I thought about it in the opposite way while writing my book. So many of us were footworkin’ to house music on the weekends, or we probably listened to our parents talk about Soul Train. So many of us have similar stories, and I wondered what experiences bind us [Black Chicagoans] together. Those similar experiences are some of the things that I wanted to talk about in this book. I wanted people to read this book and be like, ‘oh, me, too,’ or ‘we did the same thing.’

Do you mind sharing a piece of history you learned about that you weren’t aware of while writing We Are The Culture?

AN: I didn’t know much about Chicago radio like I thought I did. After Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated, the disc jockeys at WVON told people to call in and share their frustrations. They encouraged listeners not to mess up Black neighborhoods. Today, we have Twitter and other places where, in times of sadness, we can commune with each other. Some people may not use that, but I know I need that. When bad stuff happens, I personally need to be able to commune with people. So, the fact that [WVON] was such an outlet for people to be able to call in and share their grief and their pain, that’s something I just never really knew. It wasn’t like a secret story I uncovered, but it really touched me.

What do you hope resonates most with people once they get their hands on your book?

AN: I hope they can connect the past with the future better. There are so many sad narratives about Chicago. I hope people can see what we have today and see what’s possible for the future.