A bus full of local history enthusiasts was trundling down Cottage Grove Avenue a bit north of Glenwood about 6 years ago when one of the passengers asked the driver to pull in at a forest preserve driveway.

The bus passed a Betsy Ross-style American flag embedded in the ground, sculpted out of concrete with waves to give the effect that it was rippling in the wind.

Advertisement

In a thick German accent, she asked the driver to stop.

“I want to walk on this land,” she said. “This is where my father was a prisoner of war.”

Advertisement

Robin Anderson, president of the South Holland Historical Society and a member of historical societies in Lansing and Thornton, helped put the bus tour together and became acquainted with her afterward.

The woman’s father had been captured during World War II and brought to Camp Thornton, a former Civilian Conservation Corps site between Thornton and Glenwood that had been converted into a prisoner of war camp.

It was one of over 500 facilities established in the United States that collectively housed more than 400,000 enemy combatants. The majority of the prisoners were captured in 1943 when German General Erwin Rommel’s expeditionary forces surrendered in North Africa, according to a presentation by Illinois State Archaeological Survey staff archaeologist Paula Bryant, who is based in Elgin.

It made sense to bring the prisoners to the U.S., she said at a 2019 conference on Preserving U.S. Military Heritage, because it would be easier to house and feed them here than ship supplies overseas. Plus the former combatants could help relieve agricultural labor shortages, work for which they were paid under Geneva Conventions rules.

Three of the camps were in Cook County Forest Preserves, which in recent years partnered with the state Archaeological Survey to document culturally significant sites, including the CCC camps within the preserves that went on to become POW camps. Besides Camp Thornton, there was Camp Pine in Des Plaines and Camp Skokie Valley in Glenview.

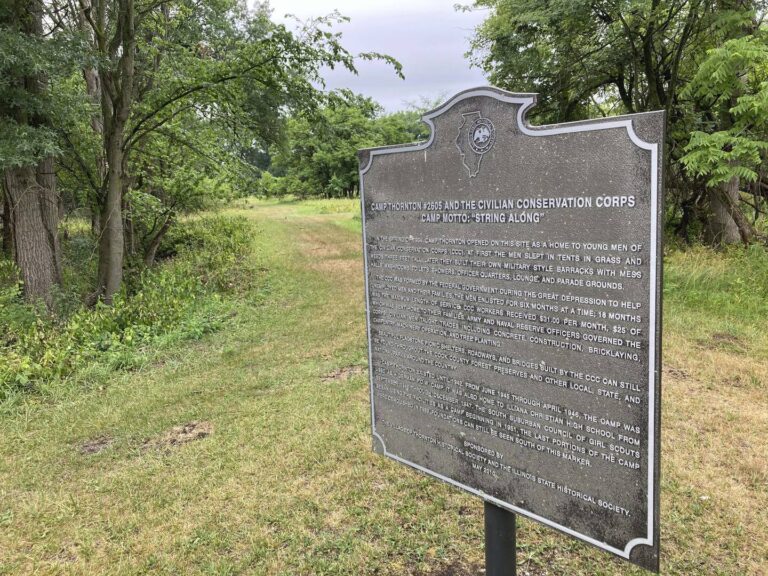

At the former Camp Thornton, that cultural history is mostly “hidden in plain sight,” Bryant said. At its peak, there were a dozen or so buildings, wide pathways and even a baseball diamond. People who know what they’re looking for still can spot remnant foundations or drainage ditches, but for the most part, the preserve now called Sweet Woods is better known for its hiking opportunities.

A historical marker placed by the Illinois State and Thornton historical societies prominently states the site’s significance, but only one aspect of the former POW camp is plainly visible: the wavy concrete flag. The concrete art, Bryant said, was created by the prisoners, who painted it in the American flag’s Betsy Ross incarnation.

Perhaps the prisoners didn’t mind creating a landmark featuring their enemy’s flag. By many contemporary accounts, they caused very little trouble.

Advertisement

Longtime Homewood resident and historian Elaine Egdorf recalled seeing the POWs being bused to workplaces, including the Libby plant in Blue Island, which was canning food to be sent to Allied armed forces overseas.

“As a little kid, we were afraid of the prisoners,” she said. “I thought they’d all look like Hitler, but seeing the faces on those buses, a lot were fair-haired. They looked like they could be someone’s big brother.”

She heard stories over the years about groups of POWS working on farms in South Holland and along Dixie Highway in Homewood where the Southgate subdivision is now.

“They never seemed to create any problem,” Egdorf said. “Frankly, I think the prisoners were relieved to be here in peace.”

Anderson unearthed a 2005 letter to the editor of The Journal of Military History in which Hickory Hills resident Thomas Pearson recalled riding bicycles to gawk at the prisoners, and being greeted by glares along with a few polite salutations in German. As the months went by, he noticed the POWs using more English.

By the end of 1946, with the war long ended, the prisoners were sent home, and their former camp became temporary classrooms for Illiana Christian High School, which was building its first edifice in Lansing.

Advertisement

From the mid-1950s through the late 1980s, the Girl Scouts of America had a camp there and the last of the Camp Thornton structures at that site were bulldozed in 1989.

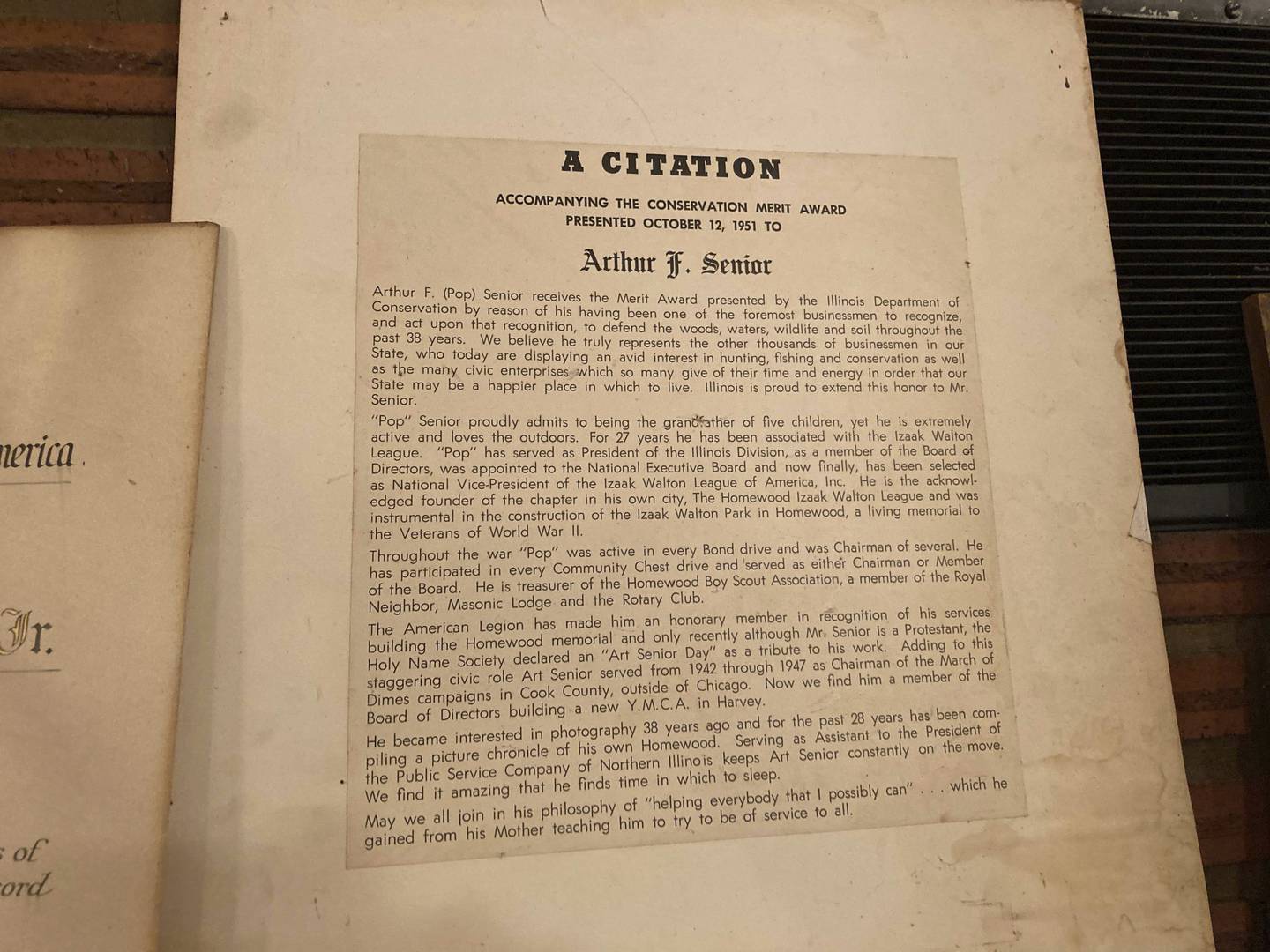

But one of the barracks built by the men from the CCC and occupied by German war prisoners remains. It’s now called Senior Hall, because of the efforts of Art Senior, a Homewood resident who helped turn 30 acres of marshy wasteland into the town’s only nature preserve 76 years ago.

Fresh from talking Illinois Central Railroad officials into donating land that had been used to excavate massive amounts of sand for rail siding projects to the village of Homewood, Senior got wind that Camp Thornton was empty, and acquired one of the barracks buildings, which was cut into segments and brought to what is now the Homewood Izaak Walton Preserve, where it was reassembled to become the new preserve’s headquarters and meeting hall, according to John Brinkman, the preserve’s president.

Brinkman said a portion of the old barracks that reflected back to the building’s original purpose by housing a live-in groundskeeper is now being converted to a museum to showcase the history of the preserve as well as its clubhouse.

Daily Southtown

Twice-weekly

News updates from the south suburbs delivered every Monday and Wednesday

He’s justifiably proud of the preserve, and the 76 years of civic-minded effort and volunteerism that went into its creation and expansion from 35 to nearly 200 acres. Much of that early work, including reassembling the former POW barracks, was completed by “out of work World War II veterans,” Brinkman said, while the building’s foundation, “a whole array of leftover telephone poles, filled with creosote” and sunk into the clay underneath, was acquired for free by “a big shot from ComEd who lived in Homewood.”

In the 1980s, according to a recent Homewood Izaak Walton newsletter, preserve leaders salvaged plumbing supplies from the recently demolished Washington Park Racetrack, that had burned down a few years before not far away on Halsted Street to add new bathrooms to the old barracks. And volunteers just this year helped replace those facilities with new ones.

Advertisement

It’s a spirit that hearkens back to the building’s origin when it was created by Civilian Conservation Corps members who later would construct stone pavilions and other lasting infrastructure on public land throughout the south suburbs.

And it’s a spirit that may have rubbed off on at least one of the men imprisoned there during World War II.

Anderson, who helped organize the local history bus tour a few years ago, said the woman who asked to stop at Sweet Woods had more to her story.

“Once the war was over and (her father) was released, he went back to Germany and brought his wife and her back to the United States to live,” Anderson said.

Landmarks is a weekly column by Paul Eisenberg exploring the people, places and things that have left an indelible mark on the Southland. He can be reached at peisenberg@tribpub.com.