By Karen Juanita Carrillo | NY Amsterdam News

Civil Rights icon Rev. Jesse Jackson, Sr., whose career took him from his early collaboration with Martin Luther King to creating the Rainbow/PUSH Coalition to two runs for the presidency and ultimately passing the torch to a new generation died Tuesday according to his family.

“Our father was a servant leader — not only to our family, but to the oppressed, the voiceless, and the overlooked around the world,” said the Jackson family in statement. “We shared him with the world, and in return, the world became part of our extended family. His unwavering belief in justice, equality, and love uplifted millions, and we ask you to honor his memory by continuing the fight for the values he lived by.”

Rev. Jackson was hospitalized at Chicago’s Northwestern Memorial Hospital on Nov. 12, for observation due to Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP), a neurodegenerative disease that was initially mistaken for Parkinson’s, according to a Rainbow/PUSH statement. He was diagnosed with PSP during a Mayo Clinic visit in April 2025. There is no current cure for the disease, so his treatment was focused on alleviating his symptoms.

In the early 1960s when young activists were fighting against race-based discrimination Jackson was among them, unaware of the role he would play in the Civil Rights Movement over the next several decades. By the time of his passing, he had lived to see the inauguration of a Black president and his work being done by thousands of people from every background.

Despite a 2017 diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease, Jackson slowed down but did not consider himself retired.

As recently as 2024, Jackson was organizing human rights campaigns to address the humanitarian crisis in Gaza, calling for the release of Israeli hostages and Palestinian prisoners, and for an end to the suffering caused by the war in Gaza.

“We are faith leaders and advocates, united in this moment of moral reckoning to affirm the sanctity of all human life,” Jackson said at the time during his “Call to Action” summit.

He was also vocal about the 2024 election and the direction politics in America was headed. “We’ll win if we vote our numbers, but if we don’t, we risk losing our democracy,” he told The New Republic in 2023. “Trump wants to pull us back into white supremacy. DeSantis is even worse. He’s a Harvard and Yale man. He knows better. There’s something more insidious about that.”

Jesse Jackson surrounded by marchers carrying signs advocating support for the Hawkins-Humphrey Bill for full employment, near the White House, Washington, D.C.

A Young Activist

Born in Greenville, S.C., on October 8, 1941, Jesse was the son of Helen Burns, a 17-year-old single mother. She later married Charles Henry Jackson, who adopted Jesse and helped raise him. After attending the University of Illinois on an athletic scholarship for one year, he transferred to North Carolina A&T College (NCAT) in Greensboro. It was there that he began working as a civil rights activist by joining the local chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). In July 1960, still a freshman, he joined seven high schoolers to walk into the whites-only Greenville County Public Library, demanding it be desegregated. They were arrested and became known as the “Greenville Eight.”

From there, Jackson grew into one of the most prominent young leaders in the movement. By 1965 he had become active in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). He had already graduated NCAT and was attending Chicago Theological Seminary. King had called for people to support his voting rights campaign in Selma, Ala., so he drove down to the site with a group of students and participated in the Selma marches which followed “Bloody Sunday”. Wanting to bring the push for civil rights back to Chicago, Jackson sought an SCLC staff position and King hired him.

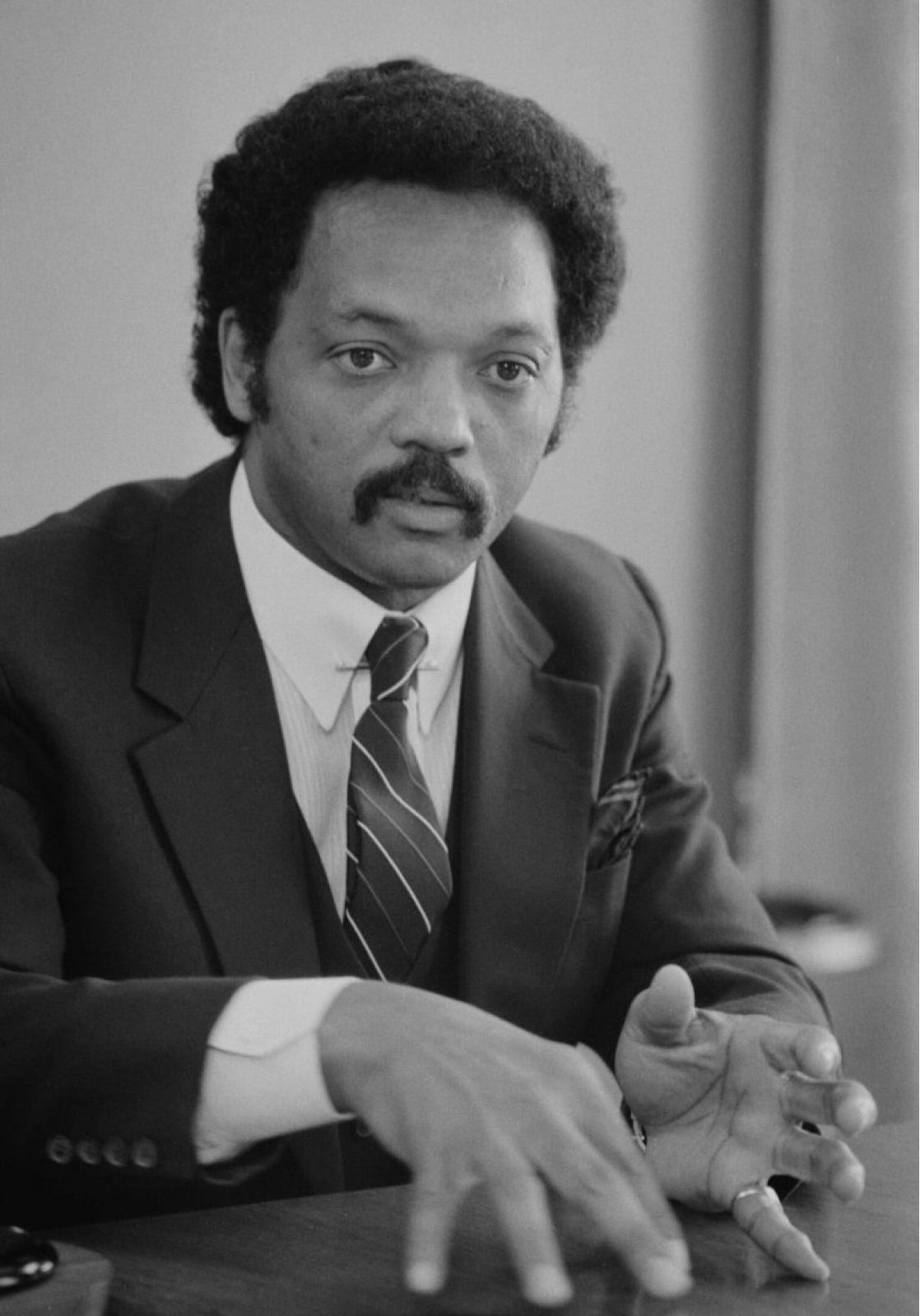

Jesse Jackson speaking during an interview in July 1, 1983. Wikimedia Commons.

AmNews Archives

The next year, when King came to Chicago to advocate against discrimination in the north, Jackson took on the role of SCLC’s economic development and empowerment program in Chicago, which became known as Operation Breadbasket. Soon after, he became its national head.

At age 26, he was in Memphis working alongside King on the Poor People’s Campaign, when he witnessed King’s assassination on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel. Jackson remembered the hours leading up to one of the most monumental moments in American history.

He described King’s mood as he prepared to give his famous “I’ve been to the mountaintop” speech at Mason Temple in Memphis. “He kind of walked back through history, as he had done that earlier that day, but talking about his own family life,” Jackson recounted in a 2008 interview with TIME.com. “We had no way of knowing the kind of pressures he was under, that he internalized and simply would not share.”

The next day, April 4, 1968, he was with several other aides of King at the Lorraine Motel when shots rang out, killing him. He was tasked with the duty of telling Corretta Scott King that her husband was dead. “Those eight or ten steps to that phone was like a long journey.”

Taking Up the Civil Rights Mantle

Jackson went on to become a prominent civil rights leader in his own right. After King’s assassination, he became an ordained Baptist minister and continued advocating for African Americans’ access to jobs as head of the SCLC’s Operation Breadbasket in Chicago. But conflicts between Jackson and Ralph Abernathy, who had taken over as SCLC president, led to Jackson’s resignation.

In 1971, Jackson founded Operation PUSH (People United to Save Humanity) to continue his civil rights work and advocate for economic improvements for the Black community. It succeeded in encouraging companies to hire more Black workers and collaborate more with Black-owned businesses. It was coupled with another project called PUSH-Excel, aimed at bettering educational standards for inner-city students.

More than a decade later, Jackson also famously united a diverse coalition of ethnic, working-class, religious, and regional progressive voters under his “Rainbow Coalition,” which he organized in 1984 to deal with the challenges brought by the economy under President Ronald Reagan. This launched his 1984 presidential campaign as a Democrat which he ran with a lack of funds and little support from the Democratic Party. However, to the surprise of many he secured 3 millions votes and won five primaries.

Jackson did face criticism for remarks he made in a private conversation that were seen as anti-semitic (which he later apologized for) and also for not distancing himself from Nation of Islam leader Minister Louis Farrakhan. But he was given a platform at that year’s Democratic National Convention in San Francisco, in which he was remembered for illustrating the strength of diversity in America.

“America is not like a blanket – one piece of unbroken cloth, the same color, the same texture, the same size,” he said. “America is more like a quilt – many patches, many pieces, many colors, many sizes, all woven and held together by a common thread. The white, the Hispanic, the black, the Arab, the Jew, the woman, the native American, the small farmer, the businessperson, the environmentalist, the peace activist, the young, the old, the lesbian, the gay and the disabled make up the American quilt.”

In the 1988 Democratic primary, he finished second — winning more votes than then-Senator Al Gore — and won the Michigan primary. In fact, Jackson won primaries and four caucuses in total receiving 6.9 million votes.

Again addressing Democrats at the party’s convention, he said:

“I’m often asked, ‘Jesse, why do you take on these tough issues? They’re not very political. We can’t win that way,’

“If an issue is morally right, it will eventually be political. It may be political and never be right. Fannie Lou Hamer didn’t have the most votes in Atlantic City, but her principles have outlasted every delegate who voted to lock her out. Rosa Parks did not have the most votes, but she was morally right. Dr. King didn’t have the most votes about the Vietnam War, but he was morally right. If we are principled first, our politics will fall in place.”

Jackson’s presidential campaigns emphasized racial and economic justice and pressured the Democratic Party to place greater emphasis on addressing issues important to working-class and low-income voters. But the emphasis after the 1988 campaign began to gradually focus on his activism rather than electoral politics. From 1991 to 1996, Jackson served as shadow senator for Washington D.C. Afterward, he merged the Rainbow Coalition with Operation PUSH to form a new organization called the Rainbow/PUSH Coalition, to address both economic inequity and to protect civil rights.

A Global Figure

Following his impressive presidential campaigns, Jesse Jackson gained international recognition. Some of it at great risk.

In 1983, Jackson successfully negotiated with Syrian officials for the release of a captured American navy pilot Lt Robert O Goodman, and several Cuban political prisoners.

Reagan criticized Jackson for interfering with foreign affairs, but he had gained a reputation in international conflict resolution and later went on a diplomatic mission to Lebanon.

In 1988, he met with Hezbollah leaders and engaged them in intensive negotiations to secure the release of nine U.S. hostages. The initiative did not result in the immediate release of the hostages, but it did spawn years of continued negotiations with Middle Eastern factions for negotiations and prisoner swaps.

In 1990, Jackson met with Iraqi President Saddam Hussein and helped negotiate the release of foreign nationals held as “human shields.” In 1997, he was appointed by President Bill Clinton and Secretary of State Madeleine Albright as the U.S.’s first-ever special envoy to promote democracy in Africa. “I could not have been special envoy to Africa until now,” Rev. Jackson was quoted as saying in a State Department release. “I’m excited by our Africa policy because it’s a source of pride, not shame.”

Jackson traveled to Yugoslavia in 1999 to negotiate the release of three U.S. prisoners of war during the Kosovo War. On January 15, 1997, Martin Luther King Jr. ‘s birthday, Rainbow PUSH launched its “Wall Street Project” which works to increase business opportunities for ethnic minorities with corporations. In 2000, President Clinton awarded Jackson the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor.

Family controversy and admission

In 2001, Jackson publicly admitted to fathering a child resulting from an extramarital affair with Rainbow/PUSH staffer Karin Stanford. However, instead of denying or hiding the situation, he was open about it, stating, “This is no time for evasions, denials or alibis. I fully accept responsibility and I am truly sorry for my actions.”

“As her mother does, I love this child very much and have assumed responsibility for her emotional and financial support since she was born,” Jackson said. “My wife, Jackie, and my children have been made aware of the child and it has been an extremely painful, trying and difficult time for them.”

Rev. Jesse Jackson. Damaso Reyes photo.

Health Challenges – A “pivot” not a retirement

Jackson announced his diagnosis with Parkinson’s disease in 2017. He stepped down as president and CEO of the Rainbow/PUSH Coalition in July 2023, after leading the organization for more than 50 years, upon turning 81 years old. He said, though that he was not done. At the 57th annual Rainbow/PUSH convention, that he we was going to “pivot” and still be a force in civil rights.

“I find fulfillment in my work. It’s my sense of purpose,” he told the Chicago Sun-Times. “I do everything with a sense of purpose.”

Rev. Jackson is survived by his wife, Jacqueline Jackson, and their children: Santita, Jesse Jr., Jonathan Luther, Yusef DuBois, and Jacqueline Lavinia. He is also survived by his daughter, Ashley, born to Stanford.