By Stacy M. Brown

Black Press USA Senior National Correspondent

Six years ago this month, Bill Cosby was sentenced to prison. For some, it was the spectacle of a fallen idol. For others, it was the raw proof that this nation, still drunk on its own lies, can summon racism from the judge’s bench, let it seep into the prosecutor’s chair, and finally stain the jury box. What was lost, what was deliberately hidden, is that Cosby—blind, wealthy, eighty years old—could have walked out untouched if he had only bent his back, signed a paper, confessed to a sin he swore he did not commit. He refused. He chose prison over surrender, isolation over capitulation. That act alone, in a country that has always demanded Black men bow their heads, ought to have been recognized as a radical declaration of dignity.

Refusing the Easy Way Out

Cosby remembered, on Let It Be Known, how they dangled freedom like meat before a starving man. “My lawyer came to me and said, the district attorney is offering you to sign a paper saying you did it… and that you wouldn’t have to do prison time,” he said. “I told my lawyer to continue with the trial… I wasn’t signing any papers or anything.” Even when caged, blind, and stripped of freedom, they offered him release if only he would renounce himself. “Sign the paper and go to these classes, and then we will let you go. Well, my signature would be in a sealed envelope, and nobody could open it.” Again, he refused. He could have chosen the coward’s path. He could have lived out his days in comfort. Instead, he chose to carry innocence as a burden, fully believing that he might never walk free again.

A Courtroom Steeped in Racism

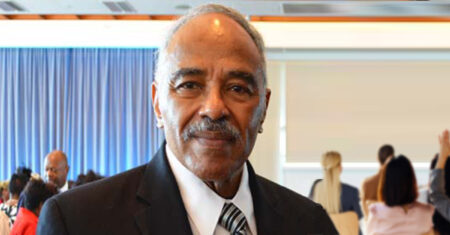

Bill and Camille Cosby, at right, arrive at the Montgomery County Courthouse in Norristown, Pa., on June 12, 2017. Cosby is on trial for sexual assault. (POOL PHOTO)

And in those courtrooms, the poison was naked. Black jurors were denied with cynical ease. A Black woman police officer was struck from service, not because she was unfit, but because she had once beaten back a false charge laid against her. At the retrial, when one Black juror was finally seated, a prosecutor spat, “You got your one.” Another juror declared Cosby guilty before hearing a single word and was still allowed to sit in judgment. And the judge—who should have been the steward of justice—was said to have whistled the theme from Kill Bill outside the jury room before the verdict in the retrial was returned.

The first trial ended in a mistrial, the jury grinding nearly 60 hours before breaking. They had leaned toward acquittal, but the judge forced them back. After the second trial ended in conviction, and when prosecutors argued he might flee because “he has a plane,” Cosby exploded once jurors left the room: “He doesn’t have a plane, you a–hole! I’m sick of him!” Never forget that prosecutors across jurisdictions passed on every other accusation. Only one case was carried forward—and even that was not about rape. The alleged victim admitted to bitterness when Valentine’s Day passed without a call. She later dialed Cosby to ask for tickets to his show for her parents. But facts were never the point. The performance of guilt was the only script the court was willing to stage.

With the Media, The Lie had No Rival.

Camille Cosby walked through those halls like a prophetess, entering a place fouled with racial contempt. She smiled, spoke softly to her husband, and left. That smile, quiet yet defiant, seemed to say: I know exactly what is happening here. And the media, hungry and complicit, huddled with the prosecutor’s mouthpiece to make certain every headline sang the same hymn of untruth. With no cameras in the room, the lie had no rival. The mention of Quaaludes covered newspapers and flooded television news, but the case was about Benadryl, 1 and a half tablets. Fiction and made-up lies were the norm at Cosby’s trials. Mainstream media pushed the narrative that Cosby “slipped” drugs into an unsuspecting woman’s beverage. However, no evidence of such was presented at trial.

Not discussed was how prevalent Quaalude use was among both sexes. The pill they called a disco biscuit was never just a drug but a mirror of America’s hunger for escape, a hunger dressed in sequins and sweat beneath the lights of Studio 54. Hugh Hefner reportedly handed them out like candy in his mansion; a promise wrapped in velvet but steeped in surrender. Andy Warhol scribbled about them in his diaries; the artist turned witness to a culture stumbling between decadence and decay. Later, Jordan Belfort made them infamous in a Wall Street gone wild, his intoxication filmed and sold as entertainment. Notably, during the second trial, when the judge stunningly allowed as many as 20 women to testify, an accuser swore she had already ingested a Quaalude before she visited Cosby with a friend in the 1970s. Another witness testified that she left her boyfriend on an exotic island after Cosby called with a job offer in Nevada, only to be miffed about Cosby’s indifference.

Still another wrote glowing words about Cosby in her autobiography, yet completely changed the story on the witness stand. When Cosby’s team wanted to put forth a witness who allegedly was with the primary accuser when the woman had come up with a ruse to “set Cosby up,” the judge refused to allow her to tell the jury. Striking was the one person who seemed, by far, the most credible witness. A chef who worked for Cosby was present on the night of the alleged incident. That chef, a meticulous older man, testified that the visit by the accuser for which Cosby was on trial occurred on his last night in Cosby’s employ. Significantly, it proved that even if something nefarious took place, which Cosby vehemently denied, it happened well outside the statute of limitations. Among other things, the state Supreme Court agreed. The justices said the trial was illegal, should never have taken place, and the verdict was wrong. The justices ordered that prosecutors refrain from going after Cosby again.

Inside Prison Walls

Behind walls meant to break him, Cosby spoke to men the world had abandoned. At SCI–Phoenix, he joined Man Up, blind, in a wheelchair, addressing those whose bodies bore chains. After speaking of his heroes, one inmate told him, “I will be your hero, Mr. Cosby.” He spoke to Men of Valor, too. “I noticed that in the Bible, the parts about Jesus, Jesus never smiled. And I want you, if you are going to do what you say you are going to do in your turnaround, make Jesus smile.”

Pound Cake Then and Now

In 2004, Cosby thundered about a boy shot dead for stealing pound cake. “And then we all run out and are outraged, the cops shouldn’t have shot him. What the hell was he doing with the pound cake in his hand?” He called out the rot of absent parenting. Now, with years and prison behind him, he said again: “They are putting us under siege.” At Phoenix, sagging pants and untied laces were forbidden. To him, these were not fashion, but chains disguised as choice. “They would rather have a picture of a youth doing nothing, not studying, and have his pants lowered.”

Camille’s Strength

It was Camille who preserved him. “My wife, Camille, is not only a very intelligent woman, but she is a woman who saved my mother’s life, and she has saved my life by continuously saying, it’s what you put in your mouth,” he said. “She makes sure that we eat like that, and that’s why, at age 88, I’m cancer-free, and I don’t have any ailments of forgetting things.” From prison, when he phoned, Camille silenced his weakness. “Whenever I called her, I just badly wanted to tell her how I felt,” Cosby said. “And she would say, ‘Just be quiet.’” He had called her strength “love and the strength of womanhood. And you could reverse it, the strength of womanhood and love.”

Giving Back

Cosby and Camille poured more than $200 million into higher education, including $20 million to Spelman College, at that time the largest gift ever given to an HBCU. Those gifts were not simply donations. They were lifelines—scholarships, endowments, futures carved from generosity.

Television and Film Legacy

Cosby broke into I Spy, the first Black co-lead in a drama. He created Fat Albert, a mirror for Black children. He built The Cosby Show, which for five years reigned supreme, showing Cliff and Clair Huxtable as what America insisted could not exist: a Black family whole, professional, and loving. A Different World sent young people surging toward HBCUs. And with Sidney Poitier, he made Uptown Saturday Night, Let’s Do It Again, A Piece of the Action—comedies still treasured in Black homes, still testaments to resilience and wit when Hollywood offered little but caricature. Cosby demanded truth on screen. When told to strip a poster from Theo’s wall—one that read “Abolish Apartheid”—he warned them: “If you do, you can take the show with it.”

The Black Press

Unlike so many others who rose to fame, Cosby never turned his back on the Black Press. His only prison interview was with the Black Press. His first long interview after release was again with the Black Press. In 2014, he said, “I only expect the black media to uphold the standards of excellence in journalism, and when you do that, you have to go in with a neutral mind.”

Deserving a Parade

Cosby’s path has been strewn with glory, grief, and betrayal. Yet what remains is a record that cannot be erased. He shattered television’s barriers, poured hundreds of millions into education, gave film and television back to his people, and stood on innocence when it would have been so easy to surrender. Through it all, he was held by Camille, and he never abandoned the Black Press. We say, give flowers to the living. Bill Cosby has earned more than flowers. For what he has given Black culture, he deserves a parade. And somewhere, the ticker tape waits.