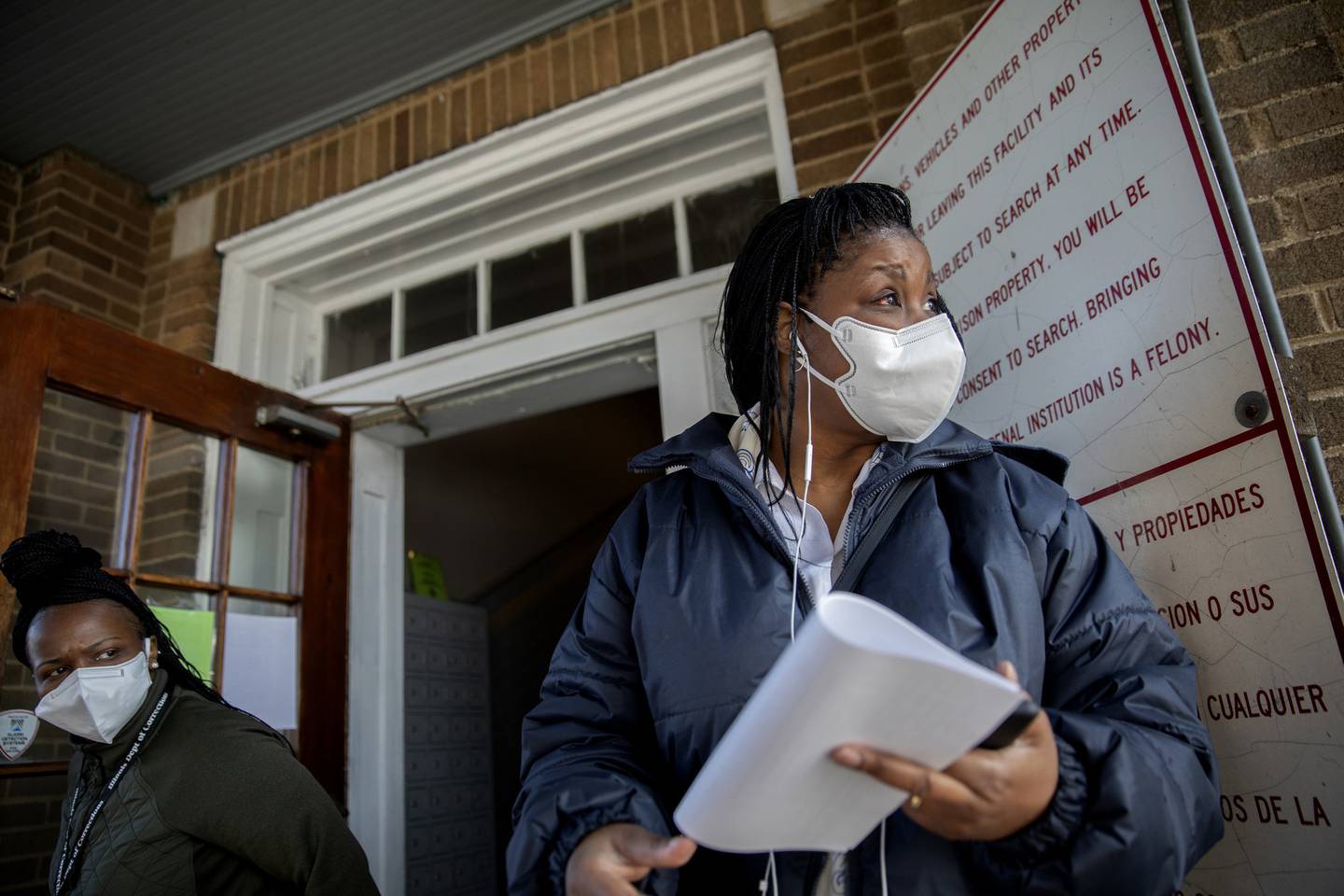

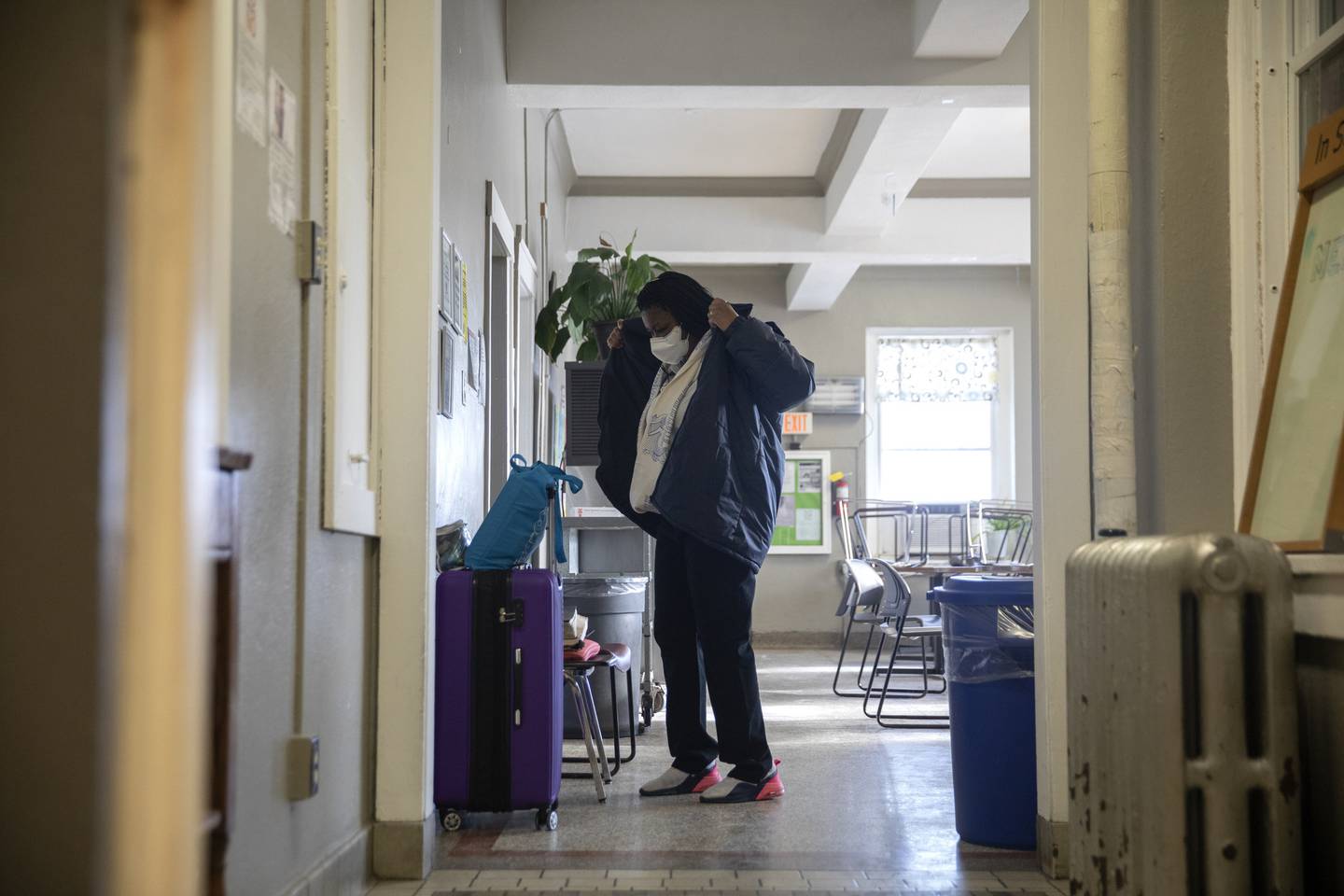

Sandra Brown walked gingerly down a walkway to the side door of Decatur Correctional Center.

She wore jeans and a hooded sweatshirt that said “The Reclamation Project,” and her hair was styled into a thick, high frohawk. Brown is tall, and moves with grace and elegance, so her hairstyle only added to her regal demeanor.

It had been 21 years since she first walked into an Illinois prison and five months since she walked out.

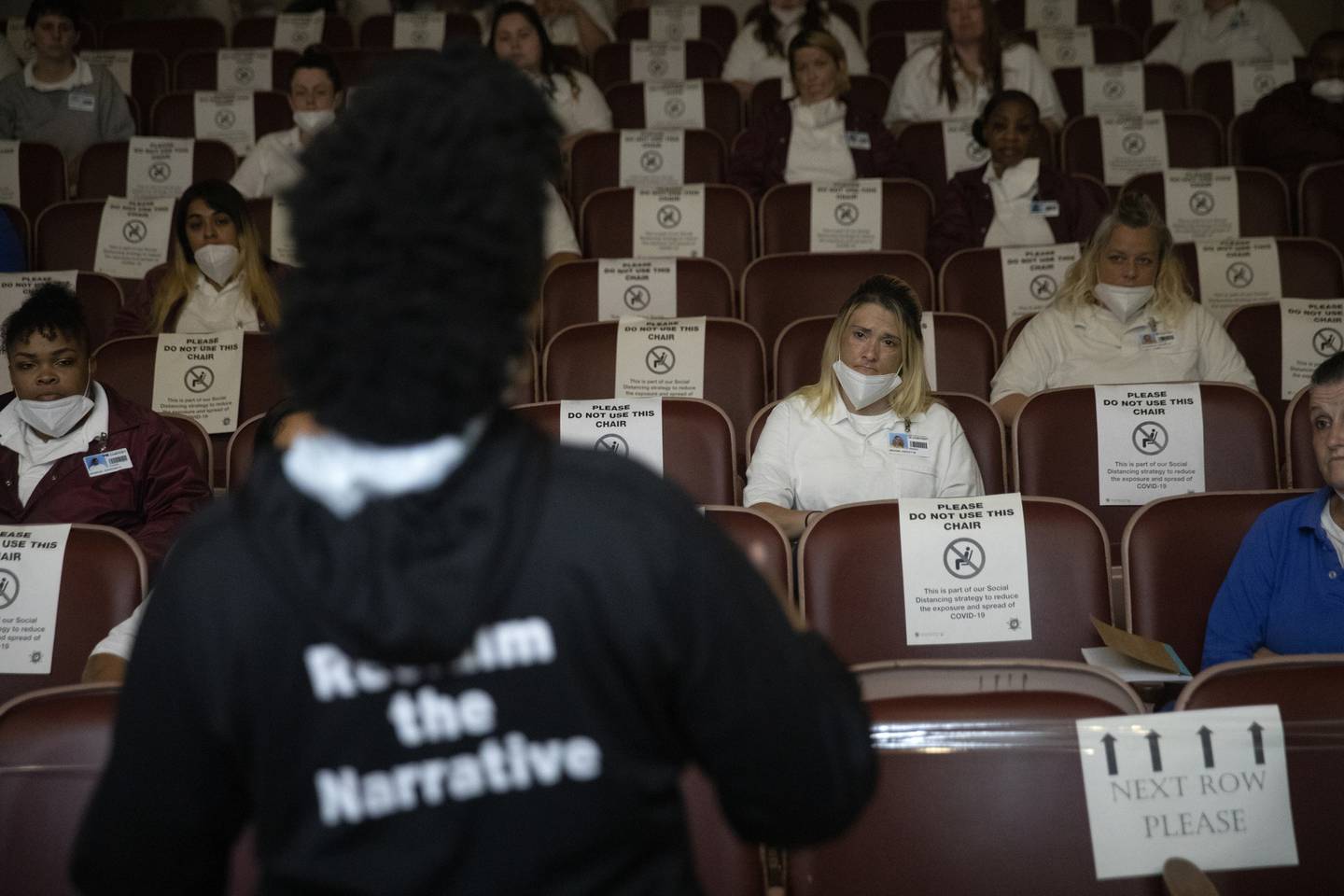

Correctional staff gathered at the security station to greet Brown as she and her group went through the slow, procedural process of checking into a prison. She was there with a film crew to lead a discussion with prisoners about the links between gender-based violence and incarceration. One by one, IDs were logged, and bags and audiovisual equipment examined.

As she waited on a wooden bench for the process to finish, a guard at the desk motioned quietly to Brown to come back over. She walked over and bent down to the small gap in the partition so she could hear the guard.

“Breathe,” Brown said the officer told her.

Brown, who had been cautioned about how unsettling a return to prison can be, sat back on the bench and raised her arm. Her hand held the slightest tremor.

“But I think it’s more from excitement,” she said with a smile, feeling relieved. “Not so much anxiety.”

Brown, against huge odds, earned a bachelor’s and a master’s degree and started a Ph.D. program while she was locked up in the Illinois Department of Corrections. The staff, both high-ranking and front-line guards, knew her and were genuinely happy to see her.

Since her release from prison in January, Brown has become a full-time education advocate, joining a number of formerly incarcerated women working to reform conditions both inside and outside of prison. They are working in government and running housing nonprofits and partnering with probation departments to provide more effective social services.

Brown, a senior adviser at the Women’s Justice Institute, is doing her work at a critical time. Key federal funding that was stripped from prison education in 1994 will be restored next year. In October an 80-page task force report pointing out critical gaps in education in Illinois prisons was released.

The Tribune has followed Brown since her release, as she settled into life outside of prison, where she has also continued writing and performing poetry. She has moved to Los Angeles to live with her husband and travels regularly to Las Vegas to reconnect with her son, whom she left behind when he was just 8 years old.

Brown, now 50, entered prison in March 2001 after she was convicted of murder for shooting the mother of her brother’s child.

Brown disputes some facts of the case that are part of the court record. But she does not challenge that she bears responsibility.

“I am always going to be sorry this happened,” Brown said in 2021, before she was released. “I am always going to be sorry.”

Brown began her sentence at a time when the Illinois female prison population was at its highest and six years after Congress passed the 1994 crime bill, which has since been widely criticized for creating harsh sentencing penalties that contributed to mass incarceration. The bill also banned use of the federal Pell Grants for prison education programs, which experts and advocates say stripped educational access for tens of thousands of prisoners.

And there were other barriers for what programming remained. Technology was exploding outside prison, but inside it was — and remains — largely unavailable. Some prisons required those serving long sentences to wait the longest for programming spots, effectively barring people like Brown. Programming for the female population also lagged behind the much larger male population.

A more sweeping problem, experts told the Tribune, is that prisons function largely for punishment not rehabilitation.

“It’s a system (that) for 200 years has been more about punishment than it is about building opportunity,” said Rebecca Ginsburg, associate professor of education policy, organization and leadership at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. “It is built into the fiber.”

By the early 2000s, higher educational opportunities had all but disappeared, except for a few outliers, Ginsburg said.

“When you read articles it sounds like such an era of despair,” Ginsburg said. “Students will talk (about) what it was like for them when the programs just (got) sucked away. It was awful, the environment at that time … and the loss of hope.”

Brown has described, in her writings, about how that hopelessness washed over her as soon as she walked into prison and was handed tattered and ill-fitting clothes. She felt her identity strip away when she looked at her ID and saw the word “INMATE” in large type totally eclipse her name at the bottom, Sandra Brown.

Brown, who had wanted to be a teacher, tried to make the best of it. She grabbed any available class. She once signed up to work as a teaching assistant for a class she couldn’t take, she recalled. She continued to serve as a TA in other classes, helping countless women, some of whom wrote to court on her behalf, describing her as a model to them.

Eventually, she decided that she’d have to look outside the prison if she was to get the education she had dreamed of. Brown researched college guidebooks in the library to find programs that offered correspondence options and wrote letters to find out whether they’d work with someone who could only hand write assignments.

Once she found programs willing to work with her, Brown tucked away cash from her work as a prison seamstress. She even volunteered to clean showers so she could collect used soap chips and save more money. Brown also scoured college guide books for scholarship opportunities.

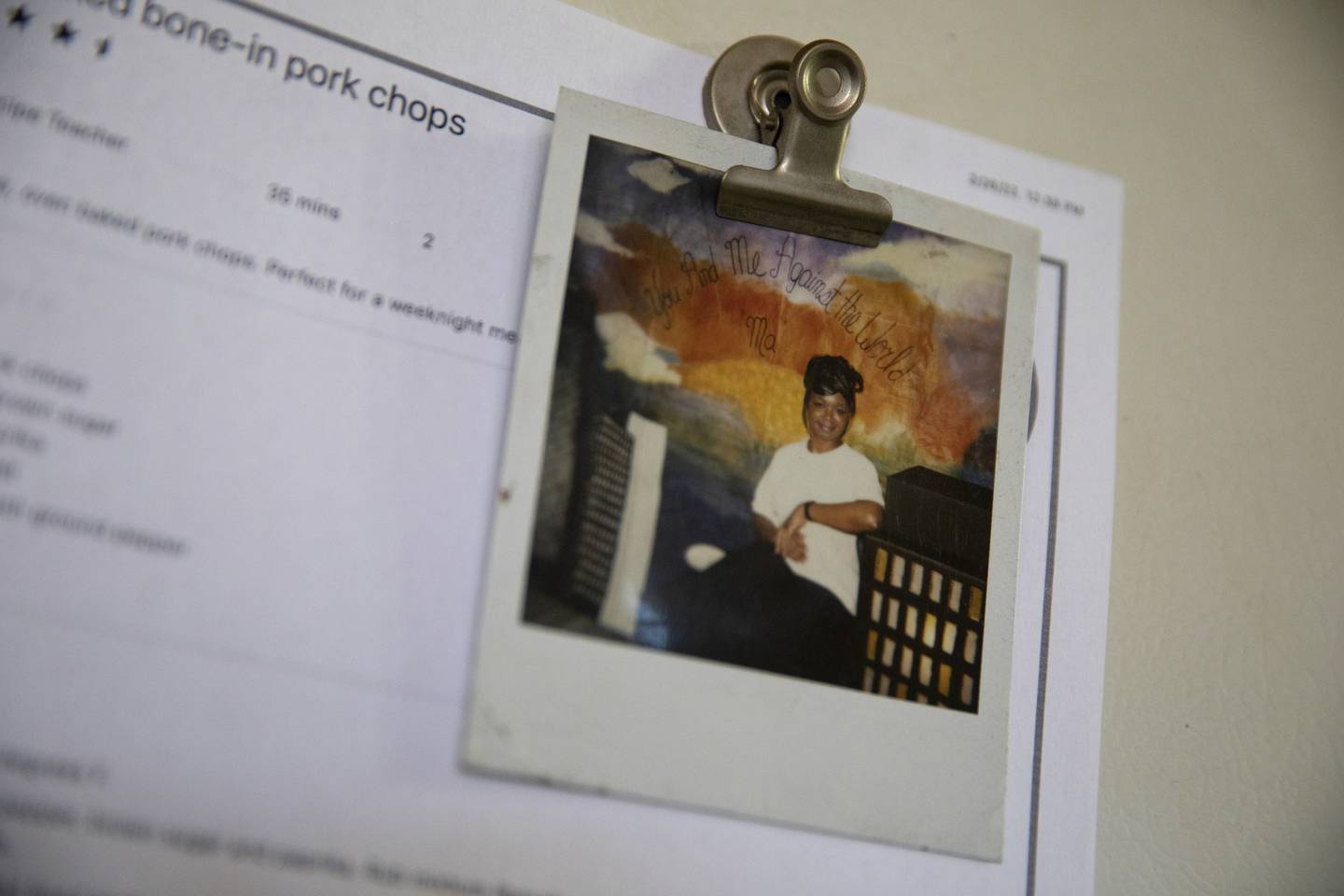

Once enrolled, she found prison staff members and officials who were willing to help. She saved $263 and bought a typewriter she named “Bessie” in honor of her grandmother, who farmed in Mississippi and is a model of strength to her, to make her assignments easier.

Brown wants people to know this part of her story because, for one, it was critical to her success. And as someone who feels judged and defined by others, she wants to be sure that the efforts of prison employees to help are recognized.

“Once in a while we found people who genuinely cared about the work they do behind the walls,” Brown said. “I was one of the fortunate ones who did.”

It was these employees who proctored her exams and sought book donations for Brown and approved the mailings so her correspondence work could get out the door. When she had trouble ordering replacement typewriter ribbons, it was a prison official who made sure the order was filled so Brown would still be able to use Bessie to complete her coursework.

It would take 11 years, but Brown earned two degrees: a bachelor’s in specialized studies, with an emphasis in literature, from Ohio University in 2012 and a master’s of arts in humanities from California State University at Dominguez Hills.

Before leaving, she started a Ph.D. program at California Coast University.

Brown said this educational journey — with Shakespeare and Nikki Giovanni and Frederick Douglass along the way — helped her confront how she wound up in prison. But those years and studies also helped her examine what so many women in prison experience, histories of domestic abuse, sexual assault, depression and PTSD.

“It is the way outside of yourself,” Brown said of her studies. “The way to understand what happened to you in the broader context. … The humanities teaches a person who is really engaged in it who they are, who they want to be and why it matters.”

Brown grew up on the West Side in Austin, one of four siblings.

Brown worked as a bus aide in Chicago Public Schools and as a classroom aide at charter schools, according to her filing with the court. She finished her high school education. She married and had a son.

But her life was filled with struggle too, according to interviews with the Tribune as well as court filings on her behalf by friends and family members. This included suicide attempts, homelessness at a young age, abuse by domestic partners, her own substance abuse and financial struggles.

In 1990, when she was 18 and pregnant, Brown was the victim of a serial rapist, who dragged her into an abandoned building in Chicago and violently assaulted her. Her assailant was caught.

Brown now says the violence she suffered played a role what happened in January 2000, when she fought with and then fatally shot the mother of her brother’s child, in a store parking lot in a Chicago suburb.

Brown acknowledges she fought with the woman, Tiffany Washington, 20, in the parking lot over the care and visitation of the baby, whom Brown said she had helped care for and raise.

In court filings for clemency and public statements about the shooting since then, Brown has described acting in self-defense.

But in court documents Cook County prosecutors described Brown as the aggressor who was looking for Washington and confronted her, first striking Washington over the head with a handgun and then discharging the gun.

Brown said her prosecution was a tense, difficult process that involved threats on her family and, she claims, pressure on her to take a plea deal or risk a longer prison sentence.

Brown eventually entered a plea of guilty to first-degree murder, but she maintains she never got a chance to argue her side of the story, something she and advocates for incarcerated women say is common.

Brown also believes that what she did that day was connected to years of suffering and trauma, “grief I never even realized was grief until after I got inside and got a little healing here and there.”

Reached by the Tribune, Washington’s aunt, Diane Lewis, said she she still carries trauma too, some 20 years later. She was there to help decide to take her niece off a breathing machine and then raised her great-niece.

Today, her great-niece lives downstate and is thriving, studying nursing and raising her own children, which gives Lewis great comfort. As for Brown, Lewis said hopes her rehabilitation is genuine.

“I am at place, I don’t have any animosity against her,” she said of Brown. “That is good if she is trying to help other women. (The murder) is the past. She has to live with that. I can’t judge. That is for God to do.”

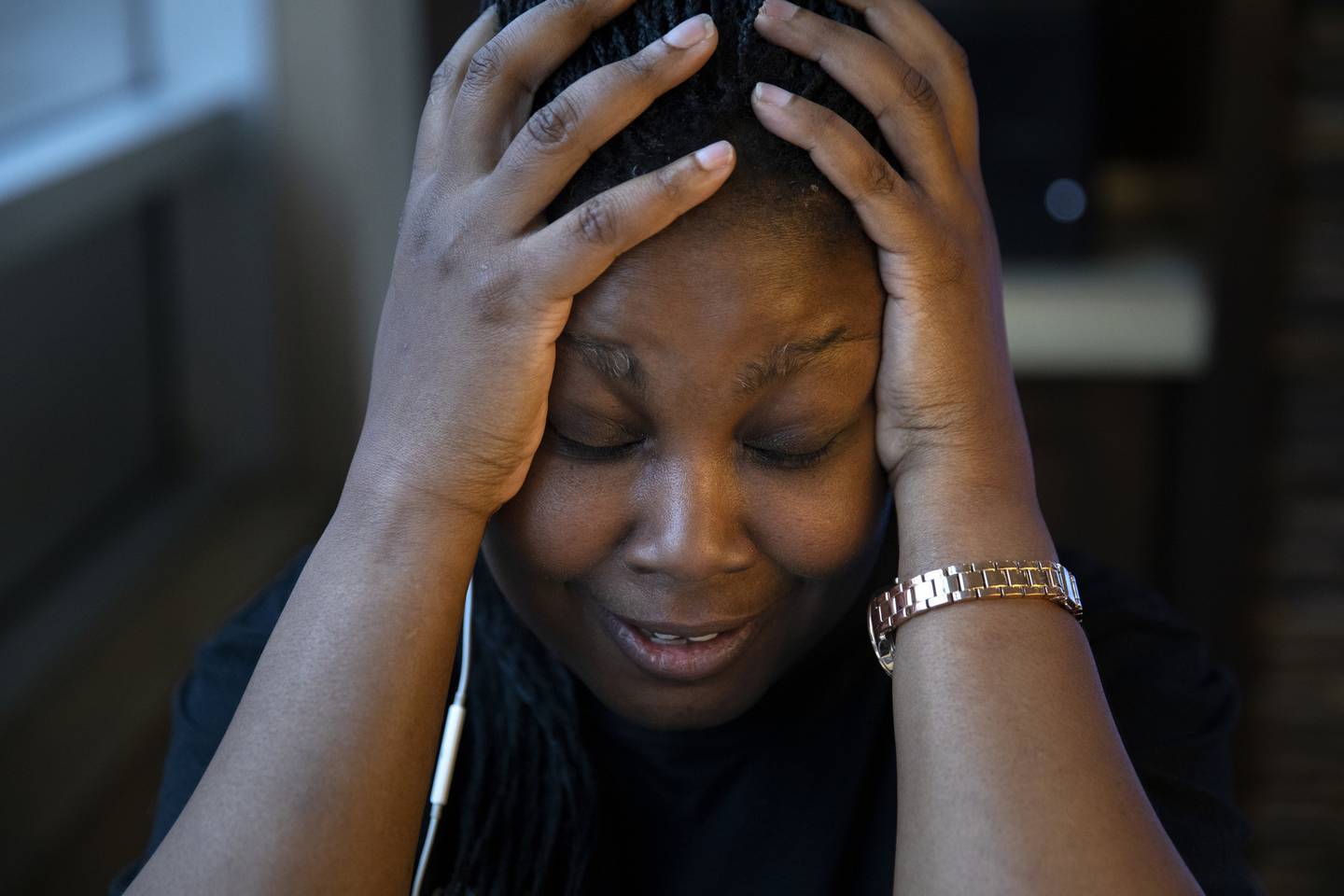

Four months after her release, Brown sat in the lobby of a Hyde Park hotel.

Minutes earlier, inside her room, Brown’s Zoom link and Wi-Fi had failed.

With barely any time to spare, she relocated to the lobby to a desktop computer. Pop music piped overhead, guests’ luggage rattled over the hard floors, and a hotel maintenance worker mopped nearby as Brown turned on the computer, found her link and looked directly into the monitor’s camera.

“I’ve been having some technical difficulties,” she said in a steady, even voice to online attendees there to learn more about prison education. “But I am honored to be here.”

Her voice gained in both strength and volume as she continued, sharing her own struggles to get educated, not to mention policy recommendations she has researched for the Women’s Justice Institute, who hired her when she was still incarcerated in IDOC.

Restore accredited college programming in Illinois prisons. Stop making prisoners who are serving the longest sentences wait at the back of the line. Increase access to grants, work study and scholarships to offset any costs. Set up a formal way for incarcerated people to find out about what programming and financial aid information is available. Create a monthly stipend for enrolled students, like other states do.

There needs to be more dedicated space for study inside prisons, as well as access to technology, she continued. What about a housing unit set aside for those enrolled in education so students can support each other, she offered.

Brown then shared the story about the showers and how she had collected other people’s leftover soap as a way to save money for her own college tuition.

“No woman should have to make that kind of choice in environments designed allegedly to help her make better choices,” she said.

After Brown finished, she let out a deep breath.

“Oh, my God,” she said. “Inside, I feel like a total wreck.”

Those who watched Brown complete her education remember her as poised and driven, having “a hustle on a whole ‘nother level,” as one said.

Maggie Burke, who formerly served as coordinator of Women and Family Services for IDOC and is the official who stepped in to help secure typewriter ribbon, saw this as well, saying Brown never stopped advocating for herself.

“What I found remarkable about her was that even after spending so much time in prison and being told ‘no’ so many times on so many things, she continued to have this bright light, this passion, this desire to learn and keep going forward,” said Burke.

Even though Brown is an outlier, she and others still wonder about how many others would have taken advantage of programming or support, if it was there.

Ginsburg, who served on the Illinois task force, estimates that fewer than 5% of Illinois prisoners have access to programming, including credited courses, vocational training or the kind of higher education degrees that Brown pursued.

But the estimate of how many have access is likely an undercount, task force members said. It is based on incomplete data and a lack of detailed information from IDOC, which led to the No. 1 recommendation in the task force’s October report: Formalize a commission immediately to study higher education and find out where and why programming is lacking.

Research shows that access to education inside prison decreases the chances a person will commit more crimes once released and increases the chance they will find a job and get paid more, the task force pointed out.

Instead, while Brown was incarcerated, she watched women come and come back, picking up new convictions and facing further setbacks. Then she saw the daughters of other incarcerated women enter the system too, having suffered from the same problems as their mothers.

As she prepared for her own release, Brown reflected on this cycle to the Tribune, questioning why the system doesn’t want to interrupt it.

“We do come back different but the question is how different, different in what way,” she said. “We either learn how to do something that will impact our lives for the better. (Or) we become passive and adopt this idea of fatalism and then we go back, costing taxpayers more money. … Or we leave out of here and learn how to be better criminals. And we’re going to be somebody’s neighbor.”

Brown now lives in Los Angeles with her husband in a small house with a bird of paradise in her yard and palm trees lining the nearby streets.

Above the mantle there is a framed diploma of Brown’s master’s of arts in humanities from California State University at Dominguez Hills.

Brown met her husband in a prison correspondence program, and opted to move to L.A. as soon as she was released. Doing that required permission from the Illinois probation services department, which agreed to transfer Brown’s case to an agent in California. Initially, Brown was put on a 10 p.m. curfew and wore an ankle monitor. She still can’t travel outside California without permission.

Brown works mostly from her home office but has been granted permission to travel frequently to Chicago for work. She has become close to her husband’s family and gotten comfortable navigating large shopping malls and groceries and learned to drive.

One of her great joys has been visits to Las Vegas to see her son, Gregory Dobbs, who was 8, when she went to prison. Today he is married and is raising four girls.

In April, during her first visit there, the slow guitar groove and longing lyrics of “Tennessee Whiskey” filled the house one afternoon as Dobbs glided around his kitchen, tending to several dishes at once. Steak, ribs in sauce, salty savory greens cooked in broth and simmered in pork, cheesy gooey macaroni, barbecued salmon and corn.

Nearby, Brown sat at the dining room table, helping one of her granddaughters on her tablet.

When her son was still in high school, he surprised Brown during one of their phone calls with news that he was leaving Chicago to live with his girlfriend’s family in Las Vegas. He needed to escape Chicago’s violence and stress, he told her.

Brown understood this. But she begged him to finish his high school education once he resettled.

Children of people who go to prison are at risk for all sorts of negative outcomes — from higher rates of chronic illness to not succeeding in school. The year Brown was arrested, in fact, Dobbs struggled in the third grade, she recalled.

And as it turns out, he never finished high school. Dobbs said he pursued his GED, however, and is working a security job at a hospital.

As Dobbs continued cooking, Brown and her granddaughters went upstairs so they could show her their bedrooms.

Once there, Kaniyah, who was in middle school, breathlessly detailed her sewing hobby and theater and math class.

She then told Brown that she had big plans for college too. UNLV or Harvard, she thinks — a safe bet and a dream school. If it happens, she will be the second person in Brown’s immediate family to go to college.

Brown was the first, she said.