By Stacy M. Brown

Black Press USA Senior National Correspondent

As the Trump administration and its disciples try to strip the nation of its memory, legendary comedian Bill Cosby said Black media cannot bend, cannot be silent, but must remind Black America that every inch of the nation’s 249 years was built with our sweat, our brilliance, our survival. Joe Black’s story is only one, yet if we allow it to vanish, we risk losing the truth of who we are.

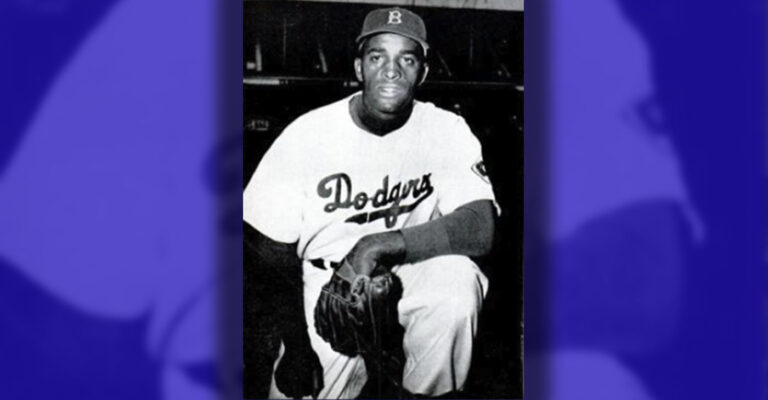

There are men whose names ring louder than the game they played, men who carried history on their backs as if it were stitched into the uniform. Joe Black was one such man. He was a boy from Plainfield who became the first Black pitcher to win a World Series game, who walked onto the mound in Dodger blue with the eyes of the country fixed upon him, and who later carried himself into classrooms, corporate suites, and pulpits with the same quiet force.

Bill Cosby remembers him not as a figure in the record books, but as the brother he never had. “Joe Black pitched for the Brooklyn Dodgers during the time Jackie Robinson was on the team, and so was Roy Campanella,” Cosby recalled. “His daughter asked me to write a preface about him; I wrote it, and then all these accusers came up and, I was told, they no longer wanted to use my preface in the story.” That daughter is Martha Jo Black, who wrote “Joe Black: More Than a Dodger.”

Cosby told how their bond began. “He came on the Dodgers and became known as a relief pitcher, but my entertaining the Black baseball players in Las Vegas during a convention, and he made himself known to me,” Cosby stated. “I found him to be a strong guy with a great sense of humor. I took him on as a big brother. When Rachel Robinson asked me to be the emcee for the Jackie Robinson Foundation, Joe was then working for Greyhound, and he made sure that he had a table.” Cosby spoke of their brotherhood in the language of fraternity and blood. “Joe also is a Q. In terms of fraternity, he’s my brother, but in my soul also; nobody else but nobody else had the humor and my feeling is that if I ever had a big brother, Joe Black was.”

The bond deepened near the end of Joe’s life, when his daughter called Cosby. “We talked on the phone. He had a house, and his daughter was taking care of him because he had problems with his prostate,” the comedian recalled. “She called me one day and she said, ‘Daddy was on the ladder, and he fell. He’s in the hospital. He’s on, I believe, morphine, a drug they give you that can cause the patient to hallucinate, and sometimes drug addicts get hooked on it. She said, ‘I’m in the hospital with Daddy, and it doesn’t look good for him. You want to talk to him?’ My heart dropped. I knew he was going, but when you get the notification, certain things happen.”

Cosby remembered that even then, Joe carried humor like a shield. “Joe had a great sense of humor and had control of it. Meaning he didn’t throw things out just to see if he was funny,” Cosby reminisced. “So she says, ‘Daddy, it’s Bill on the phone, he wants to say something to you.’ He said (in a very faint voice), ‘Hey,’ I said, ‘how you doing. I know it’s a stupid question, but how you doing?’ he said, ‘they’re trying to make it easier for me to go wherever I’m going.’ I said, ok, I said, your daughter told me you wanted to talk to me. He said, ‘Yeah. How are you doing?’ I said, this is getting stupid. He said, ‘really?’ I said, yeah, because she said you fell down on the ladder and you’ve been ripping the IVs out of your arm and misbehaving. He said it’s just the sign that I’m going. I said nothing, just let the silence sit. And he said, ‘I want you to do me a favor.’”

Cosby tried to answer the call with laughter. “I said before I do you a favor I’m out at your house and I got the map you gave me – something I was making up to humor him – I said I got the map you gave me and I walked it in the backyard and I found the tree you’re talking about and I started to dig, and I dig and I dig and I dig and my back hurts. The money is not there! And he said, ‘wrong house!’” The faint laughter in that hospital room turned into a covenant between two men.

“He said, ‘I want you to do me a favor.’ I said OK,” Cosby recalled. “He said, ‘I’m on the mound, I want you on the hot corner.’ And I said now before you put me on the hot corner, I’m going to go, but I want you to know I played sandlot baseball and I played second base and I want you to know that I was always afraid of a hot ground ball coming to me and as I bend over to catch it, it hits something and jumped up and hit me in the face. I never wanted that, I always turned my head; I understand from coaches you are supposed to look it into the glove, but I’m not about to put my face down there and look it in. I said but Joe, for you I’m on the hot base, and if anything comes to me, I don’t care who hits it, I’m going to look it in. he said, ‘Let’s go!’ that was the last words from him.” Cosby carried those words into his own storm. “Sitting through the trial, the hatred, sitting through all of that, and when that judge read all of Dante’s Inferno, and I’m listening, and he says you have any regrets? I shook my head because Joe’s voice said, ‘Let’s go!’ Joe passed that same day,” Cosby sadly recounted.

There was more to Joe Black than statistics and more than the World Series victory that newspapers still cite. He had been an officer in the Army, a teacher in Plainfield, a Greyhound executive who opened doors for Black workers and students, a columnist who urged young people to value education, and a man who carried his daughter Martha Jo through childhood with devotion when courts seldom granted fathers custody. He was also the man who told Jackie Robinson’s story in ways the white press did not record. He spoke of teammates holding Jackie back from fights, of players forming a wall to keep him from stepping into violence, of the toll carried by those chosen to be symbols.

“Because it’s always about them,” Cosby said. “What does that do to us?”

What it did to Joe Black was give him the conviction that history must be guarded. Cosby spoke passionately of Josh Gibson, of the Negro Leagues, and of Dunbar High School in Washington. The Cosby Show icon insisted that these stories must be kept with a clenched fist, placed in the hands of the next generation, stored in HBCUs where young people could know the truth of who they were.

At 88, Cosby holds fast to Black’s last words. Not a farewell, not resignation, but a command.

“Let’s go.”